JEO 10 - What to Watch for in 2026

A monthly newsletter about the space, Earth observation, and geospatial industries in Japan. This issue outlines some stories to follow in 2026 including launch, satellites, deep space, debris management, the Japan Space Strategy fund, supply chains, and a major open source conference

Welcome to Japan Earth Observer (JEO), a monthly newsletter about the space, Earth observation, and geospatial industries in Japan. This issue outlines some stories to follow in 2026 including launch, satellites, deep space, debris management, the Japan Space Strategy fund, supply chains, and a major open source conference.

What to Watch for in 2026

2025 was an eventful year, and we can expect more of the same in 2026. Here’s a run-down of what to keep an eye on in Japan.

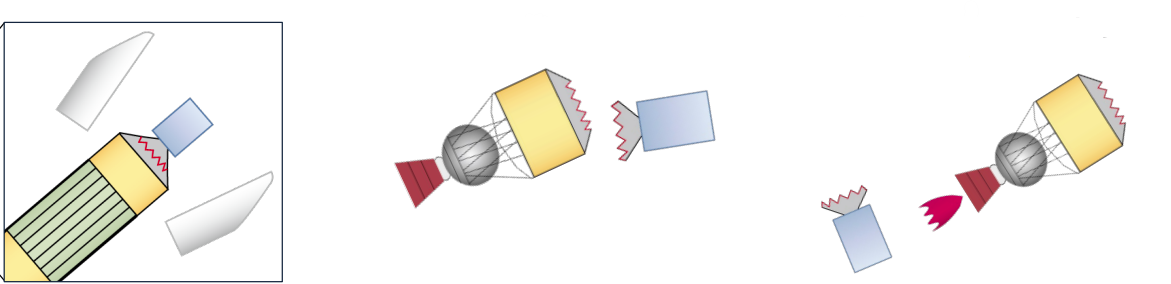

QZS-7 and the H3 rocket return to launch

JAXA, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (三菱重工業株式会社), Mitsubishi Electric (三菱電機株式会社), and their partners had a significant setback in December when the second stage of the eighth launch of the H3 rocket failed [Space.com], and the QZS-5 navigation satellite it was carrying was lost. This was an expensive satellite, and its loss delays the completion of the 7-satellite configuration of the QZSS [JEO] that Japan needs to be able to have a standalone global navigation system. It is also a setback for the H3 rocket, which, after an initial failure, has had an otherwise successful launch record. The initial reports have been that when the payload fairing separated, it may have impacted the second stage and damaged the fuel tanks that supply the engines. However, the situation remains under investigation and in the meantime, the planned Feb 1 launch of the QZS-7 satellite, has been delayed [JAXA]. It is unclear how long it will take Mitsubishi Electric to manufacture a new satellite to replace the one that was lost, but it will be even more important for JAXA and MHI to return the H3 rocket to service. In addition to QZS-7 and at least one HTV-X cargo trip to the ISS, Japan is planning a high profile Martian Moons eXploration (MMX) mission in 2026.

Diagram of H3 second stage failure. Source: JAXA

Will Epsilon S rocket development get back on track?

The flagship H-series liquid-fuel rockets developed by Mitsubishi Heaving Industries for JAXA receive a lot of attention. However, the lesser-known Epsilon rocket series is equally important for Japan’s effort to maintain a sustainable domestic launch capacity. Epsilon has long been developed by IHI Aerospace. The solid-fueled rockets are aimed at cost-effectively launching small and medium-sized satellites to low Earth orbit with scientific and Earth observation payloads. However, the next generation Epsilon S has experienced two ground test failures that ended in explosions in 2023 and 2024. The inability of Epsilon S to get off the ground has forced JAXA to contract with Rocket Lab for research and science payloads that have been waiting for Epsilon to return to flight. In 2026 JAXA will both need to close out its investigation and determine if development of Epsilon S should proceed or if the program should revert to the previous, lower-powered second stage. I expect that the review will continue but that JAXA [NHK] will revert to using the previous, tested second stage in order to get Epsilon flying again.

Will any of Japan’s commercial rocket startups reach orbit?

Rockets developed directly for JAXA are not the only ones facing tests and challenges in 2026. Commercial rocket developer Space One Co (スペースワン) is currently planning the third attempt to launch its solid-fuel KAIROS vehicle [World Insight] on 25 Feb from Spaceport Kii. A lot is riding on this launch. Spaceport Kii is the first fully private launch facility but has yet to host a successful launch. Space One has several prominent investors, including Canon, IHI Aerospace, Shimizu, and the Development Bank of Japan, that would doubtless like to see some prospect of a return on their investment. KAIROS will carry five satellites from Taiwan, Terra Space Co., Space Cubics, ArkEdge Space, and a satellite developed by Tokyo students.

Interstellar, another Japanese rocket launch aspirant, is targeting 2027 for its maiden launch but plans to complete critical engine tests as well as work on a new launchpad at the Hokkaido Spaceport in 2026. They just closed a US $130 million series F funding round on 16 Jan 2026.

Innovative Space Carrier (ISC) was recently forced to shift strategy after regulatory sclerosis in the US delayed a planned test at Spaceport America using rocket engine technology licensed from Ursa Major. ISC will now develop an engine using domestic technology [ISC] and carry out tests at Asahi Kasei’s facility in Shiga Prefecture. It now plans to launch from Hokkaido Spaceport in 2028.

Sierra Space is not a Japanese launch company, but the Japanese trading company Kanematsu (兼松株式会社), MUFG Bank, and Tokio Marine & Nichido are key investors. The first launch of the Dream Chaser spaceplane is now scheduled for late 2026 atop a ULA Vulcan rocket from Vandenberg Space Force Base.

Sierra Space’s first Dream Chaser space plane, Tenacity, in the hanger. Credit: Sierra Space

Astroscale will attempt both deorbit and refueling operations

Astroscale UK completed a critical design review in June 2025 [Astroscale] for the ELSA-M spacecraft to conduct an active debris removal mission. The ELSA-M launch is expected for 2026 and will attempt to approach, dock, de-orbit, and then release a defunct Eutelsat OneWeb satellite. Astroscale’s mission is part of a broader effort to reduce debris in low Earth orbit (LEO)

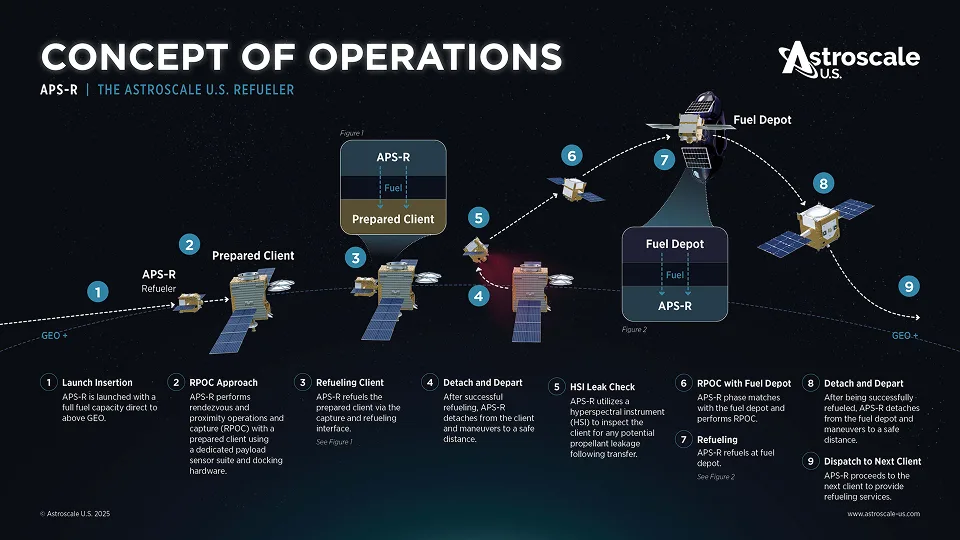

In addition, Astroscale US is expected to launch its first Refueler mission that will deliver hydrazine fuel to two U.S. Space Force satellites in geostationary orbit (36,000 km). A Chinese mission demonstrated the feasibility of such a feat in 2025, so this won't be the first mission of its kind, and other companies are attempting to develop similar capabilities, including Northrup Grumman’s SpaceLogistics subsidiary [Air and Space Forces]. However, Astroscale’s mission will be more complex than anything previously attempted. The two target Tetra-5 satellites are equipped with a refueling port (Rapidly Attachable Fluid Transfer Interface or RAFTI) developed by partner Orbit Fab. The 300 kg Astroscale APS-R Refueler spacecraft will approach the first Tetra-5, attach to the RAFTI, and transfer fuel. It will then back away and scan for leaks before moving on to rendezvous with an Orbit Fab fuel depot - essentially, an orbiting gas station - refill its tank and then travel to a second satellite to deliver a second load of fuel to another satellite. For this mission, the Orbital Fab fuel depot will launch on the same flight as the Astroscale APS-R spacecraft, but in the future, we can expect fuel depots like this to be launched in advance and maintained as long-term storage.

There are more than 500 large satellites in geostationary orbit, and they tend to be both expensive and highly engineered spacecraft that carry out a range of telecommunications, broadcasting, weather observation, navigation, and other crucial functions. Every year 10 to 20 reach end-of-life due to lack of fuel, and a few a year also experience malfunctions. The ability to keep more of these satellites operating longer will reduce both the cost of each mission and the need to launch replacements. The capabilities being developed by Astroscale, its partners, and its competitors are aimed at building a commercial ecosystem that can support greater mission longevity, sustainability, and resilience. The U.S. Space Force recently announced that it expects to require standardized refueling ports [Breaking Defense] on its next generation RG-XX constellation. Astroscale has already embedded its standardized docking plate on hundreds of satellites and was recently awarded a patent for no-fuel approaches to failed satellites. As the capabilities are developed, we can expect the development of global standards that will enable interoperability.

Astroscale Refueler concept of operations. Credit: Astroscale

Space debris and responses to it will get real

At this point in time, even if humanity does not launch any more satellites into low Earth orbit, the amount of debris will increase due to collisions. SpaceX has almost 10,000 Starlink satellites in orbit and is aiming for a 45,000 satellite constellation with 30,000 already approved. Amazon Leo has almost 200 satellites and is building toward a constellation of 3,000. These both pale in comparison to constellations planned by Chinese companies. Guowang is building toward a 13,000 and Qianfan (Thousand Sails) is aiming for about 15,000, but China just filed with the ITU for two additional constellations, designated CTC-1 & CTC-2: these new, massive applications from a joint government-industry body request nearly 97,000 satellites each, totaling over 193,000. A recent report by the World Economic Forum [WEF] estimates that, even without major collisions, LEO congestion will cost the industry US$25.8 - 42.3 billion [Payload] over the next ten years through the service interruptions, hardware losses and replacements, and the cost of maneuvering to avoid potential collisions.

Costs are likely to be one driver, but government regulation will be another. While the U.S. has been slower to add new space sustainability regulations, the ESA has set a goal of zero new space debris from European missions by 2030. The Zero Debris Charter set both high-level guiding principles and specific targets to get to Zero Debris by 2030.

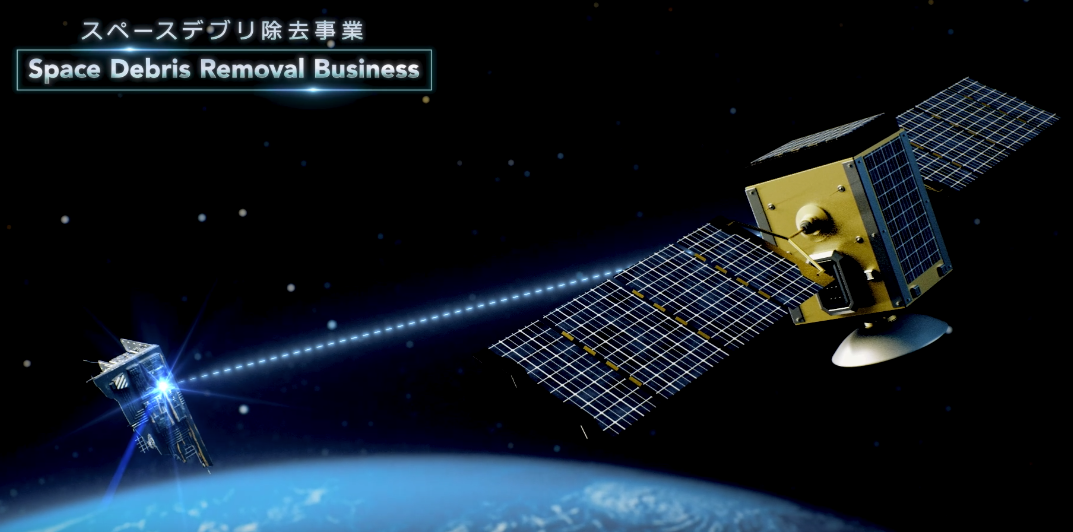

In addition to Astroscale’s plans described above, there are other Japanese firms building debris tracking, debris mitigation, and de-orbit tests in 2026.

- Axelspace’s D-SAIL concept was launched in December as part of the JAXA RAISE-4 mission. The D-SAIL satellite will deploy a sail-like membrane [Axelspace] with an area of 2m² and several tens of microns thick. The membrane is expected to increase atmospheric resistance and thereby gradually lower the satellite’s altitude, accelerating its re-entry into the atmosphere.

- BULL has raised a seed round to support development of its own sail-inspired space debris prevention devices.

- Orbital Lasers, a spinoff from SKY Perfect JSAT, is developing debris removal lasers as well as LIDAR mapping tools.

- Power Laser Technology is also working on using lasers for debris removal.

- LSAS Tech is developing debris tracking, trajectory, and orbit analysis and simulation software

- Space Weather Company is developing debris tracking radar.

- Star Signal Solutions is building tools for space traffic and debris management, collision avoidance, and space situational awareness. It was recently awarded a JAXA Space Strategy Fund contract to build ultra-small debris detection technology using optical fences.

Illustration of Orbital Lasers concept for nudging debris into the atmosphere. Source: Orbital Lasers

While Astroscale enjoys a clear early mover advantage, and several Japanese companies are developing technology for managing debris, other companies in North America and Europe are developing similar capabilities. Europe’s D-Orbit just closed a D series funding round of US$53 million, and while much of this funding is expected to be spent on M&A and developing its in-orbit computing infrastructure, it is also investing in developing the robotics necessary for complex in-orbit activities, such as satellite debris mitigation and servicing. And U.S.-based Starfish Space just inked a US$52.5 million deal to use its Otter spacecraft and software to deorbit a U.S. Space Force satellite in its Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture (PWSA) in 2027. I think we can expect this to be a competitive sector with many developments arriving in 2026 and beyond.

Will the Space Strategy Fund change under Takaichi?

March 31 will mark the end of the Japanese fiscal year 2025 and Year 2 of the Japan Space Strategy Fund (宇宙戦略基金) [JEO 3]. A lot of awards have not yet been announced for Year 2 but the following have been posted:

| Theme | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 宇宙輸送 Space Transportation | Solicitation Date | Results Date | Awards |

| System technology for smart launch sites |

2025.08.22 | Pending | |

| Technologies for ensuring safety of crewed space transportation systems |

2025.08.08 | Pending | |

| Feasibility study on facilities contributing to high-frequency launches |

2025.07.25 | 2025.11.21 | IHI Aerospace |

| Innovation in rocket manufacturing processes for high-frequency launches |

2025.06.13 | 2025.12.19 | IHI Corporation Akahoshi Industry SPACE ONE Toray Carbon Magic Tokuda Industry Hikari Manufacture Fuji Seiki Hokuto UACJ |

| Rocket components that contribute to high-frequency launches |

2025.05.16 | 2025.11.21 | Eagle Industry Air Water NEC Space Technology Sinfonia Technology Suiho Space Innovations Space BD Mjolnir Spaceworks |

| 衛星等 Satellites | Solicitation Date | Results Date | Awards |

| Frequency sharing technologies for satellite to ground communication |

2025.08.22 | 2026.01.16 | Rakuten Mobile |

| Innovative satellite mission technology demonstration support |

2025.08.08 | Pending | |

| Technology for next-generation Earth observation satellites |

2025.08.08 | Pending | |

| Technology for orbital transfer, in-orbit refueling, and space logistics |

2025.08.08 | 2026.01.23 | NEC Corporation Pale Blue Mitsubishi Electric Astroscale Yokohama National Univ. |

| Accelerate implementation of satellite data utilization systems |

2025.07.11 | Pending | |

| Terminal interconnection technology for satellite optical communications |

2025.07.11 | 2025.12.19 | Warpspace |

| Internationally competitive communications payload technologies |

2025.07.11 | 2025.12.19 | Mitsubishi Electric |

| Technologies for in orbit manufacturing, object removal, and space situational awareness |

2025.06.27 | 2025.11.28 | Toray Mitsubishi Electric Power Laser (2) IHI Corporation Star Signal Solutions |

| Data relay service using satellite optical communications |

2025.06.27 | 2025.11.21 | Space Compass |

| Advanced technologies for accelerating the use of Earth environment satellite data |

2025.06.13 | 2025.12.19 | Space Data Tellus Preferred Networks |

| Feasibility study on the development and manufacturing of satellite buses and optical communication terminals |

2025.05.16 | 2025.10.10 | National Institute of Information and Communications Technology (NICT) NEC Corporation Mitsubishi Electric |

| 探査等 Exploration | Solicitation Date | Results Date | Awards |

| High-precision landing technology in the lunar polar regions |

2025.07.25 | 2026.01.16 | ispace |

| Orbital data center construction technology |

2025.07.25 | 2026.01.16 | SpaceBlast |

| Technologies for efficient use of on-orbit research facilities |

2025.06.27 | 2025.11.28 | Japan LEO Shachu |

| High-frequency material recovery system technology |

2025.06.13 | 2025.11.07 | ElevationSpace |

| Foundational technologies for lunar infrastructure construction |

2025.05.16 | 2025.10.10 | University of Tokyo Tohoku University Ritumeikan University |

| 分野共通 Common Areas | Solicitation Date | Results Date | Awards |

| SX Core Area Development Research "SX-ARK" |

2025.09.12 | Pending | |

| Solving environmental testing challenges for spacecraft |

2025.08.22 | 2026.02.13 | IMV Corp SEESE Corp. High Energy Accelerator Research Organization (KEK) Japan Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA) (2) National Research and Development Agency (RIKEN) National Institutes for Quantum and Radiological Science and Technology (QST) |

| SX-CRANE, a space-transfer and new industry seeds creation center |

2025.08.08 | 2026.02.06 | Tokyo Univ. of Marine Science and Technology Tokyo Univ. of Science (2) Yamagata Univ. Waseda Univ. |

From a brief overview of Year 1 and Year 2 awards, I have a few observations:

-

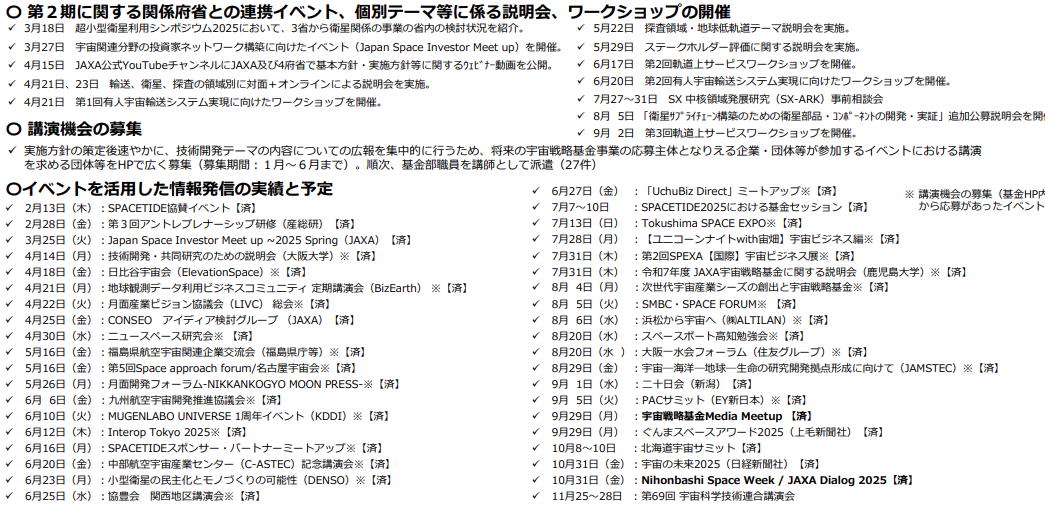

Public, transparent process - JAXA has worked hard to describe each topic in depth with both online and in-person briefings during the spring and summer. Further, it has published selection criteria, results, and who sits on each selection committee. This year, it also published a compendium of interim results for all recipients of Year 1 funding. Finally, it has proactively participated in dozens of public outreach events across the country. Transparency helps to build trust, and JAXA invests a lot of effort in this.

A list of Fund-related public workshops and outreach events by JAXA in 2025. Source: JAXA -

Collaboration is rewarded - From reviewing the Year 1 compendium, most successful awards are collaborations between at least two firms. Further, a university is part of the vast majority of successful teams.

-

International collaboration is part of the plan - While the Strategy Fund can only provide direct funding awards to domestic Japanese organizations, JAXA understands that the potential market for innovative products and services is a global one. Part of its approach includes active outreach to international space agencies and potentially co-funding collaborations between Japanese firms and those in other countries. JAXA already organized a B2B matchmaking event with the UK Space Agency and is committed to organizing more of these.

-

Open to feedback - The Strategy Fund is overseen by a Steering Committee that makes recommendations for changes. In January, JAXA published both the recommendations and their proposed actions. The January 2025 recommendations have already led to Year 2 improvements:

- Improve transparency and outreach with a more proactive industry engagement process and announcement of solicitation dates at the beginning of the fiscal year. JAXA has clearly acted on this in the Year 2 process.

- Set a broader array of themes - I don't see this in the themes, but JAXA is forecasting that they will make 140 awards in Year 2 (there were ~50 in Year 1). Many Year 2 awards have not yet been made, so the jury is out on this one

- Improve international collaboration - This led directly to the new international cooperation and co-funding program described above

- Strengthen government procurement coordination

The January 2026 Steering Committee recommendations have repeated some similar themes, including better government procurement communication and coordination, more support for securing overseas market access, and developing mechanisms to attract private capital. As Year 1 awardees are approaching their first formal “stage-gate” evaluations, the steering committee is also urging discipline in terms of terminating contracts that are not seeing results and concentrating funds on the most promising efforts.

-

Low risk tolerance - There are some exceptions, but the majority of the recipients are established firms, prominent research universities, or well-funded startups. The Space Strategy Fund has three key goals: 1) expand the domestic space market by supporting startups, innovation, and commercialization of space; 2) address societal challenges in energy, environment, agriculture, disaster management, and public health; and 3) pioneer science and technology frontiers. Bold innovation rarely arises in established, incumbent firms. Japan has suffered for decades from sclerotic science and technology development, and if it is going to increase the productivity of its economy while facing a declining population, it will have to make a lot of bold bets on young, fast-growing innovators. An anemic venture capital ecosystem means that the government is often a key source of funding for innovative startups. Growing the space ecosystem will require disruption of the status quo industry. Some will fail, but some will become the large companies of the future. The Strategy Fund awards thus far look like safe stewardship of public funds, but they also look like they are reinforcing the status quo industrial structure, rather than betting on startups that will help pioneer the frontiers.

-

Infrastructure predominates - If we think about the space industry structure as including three layers - Infrastructure, Distribution, and Applications - most of the Fund’s investment in Years 1 and 2 is going to infrastructure: rockets, satellites, and the components and materials used to make them. Again, there are exceptions: Ocean Eyes, Umitron, Marble Visions, Pacific Consultants, and Space Tech Accelerator clearly fall into the Applications layer. However, funds for this type of work were all grouped under a single feasibility study theme in Year 1, and there are no themes or awards focused on building the Distribution platforms that often become the hubs around which high value applications are built.

One of the Fund’s goals is “address societal challenges in energy, environment, agriculture, disaster management, and public health” and this is also getting short shrift in the selection of both themes and awards.

Conventional wisdom is that Japan excels at “making things” (mono-tsukuri 物創り) and that is certainly true, but Japan also boasts an incredible track record for services innovation and a great deal of future societal value will be in Applications and Distribution. By short-changing these layers of the value chain, I believe the Space Strategy Fund is demonstrating an incomplete strategy.

Japan has a new Prime Minister and PM Takaichi has outlined an aggressive plan to expand industrial policy R&D programs like the Space Strategy Fund to 17 industries across five cross-cutting themes:

- AI, Semiconductors, and Advanced Materials

- Energy, Food, and Logistics Security

- Defense and Security Infrastructure

- National Infrastructure and Regional Revitalization

- Biotechnology and Healthcare

I think it’s unlikely the Takaichi administration will change the direction of the Space Strategy Fund. Rather, it seems more likely that it will be a model on which she will double-down on the overall approach to national industrial policy. After calling a snap election in early February, she just won the biggest majority in Japanese electoral history, and she will now have the legislative support to pursue this and a range of other R&D investment priorities.

Axelspace, Synspective, iQPS, and IHI constellation build outs

Japan’s commercial Earth observation satellite firms are building out their constellations, and three firms, in particular, are set to make significant progress in 2026.

Axelspace IPO-ed in 2025 and plans to launch seven next-generation GRUS-3 imagery satellites. It successfully launched the GRUS-3α pathfinder satellite in June 2025, and the production constellation will integrate learnings from the prototype. These new satellites will capture imagery with 2.2 meter resolution and will be multispectral and will capture optical (RGB) bands as well as Red Edge, Near Infrared, and a “Coastal Blue” band for coastal and underwater monitoring. The imagery will significantly expand Axelspace’s AxelGlobe imagery service, adding 2.3 million square kilometers of imagery per day from sun-synchronous orbits of 585 km. This is not global coverage but it is almost the land area of China or Australia.

Synspective is aiming to build a constellation of 30 SAR satellites. They launched one satellite on a Rocket Lab vehicle in 2025, and they now have an active constellation of four birds and signed launch contracts with Rocket Lab for 21 more, plus additional launch contracts with Exolaunch (a launch broker) and SpaceX.

iQPS is also building a constellation of SAR satellites, aiming for 24 birds by 2027. They have successfully launched 13 satellites and nine are currently operational, six of which were launched in 2025 on Rocket Lab vehicles. They have contracts with RocketLab for at least five more launches.

IHI Corporation is taking a different route, contracting with other companies to build a constellation that combines SAR, infrared, optical, multispectral, and hyperspectral sensors. It is having SAR satellites built by Finnish firm ICEYE [Nikkei Asia] at a facility in Japan and expects to have the first four launched in FY2026. It has a partnership with SatVu for thermal infrared [Payload] satellites and with Surrey Satellite Technology (SSTI) for the others.

Axelspace, Synspective, and iQPS are also part of a new JMoD contract (see below), so 2026 will be a busy year for them.

SKY Perfect JSAT will receive its first Pelican from Planet

SKY Perfect JSAT (スカイパーJSAT) signed a $230m contract with Planet Labs in 2025 to build and launch a dedicated constellation of Planet’s latest Pelican Earth observation satellites. Planet already has some Pelicans in orbit and plans a total constellation of 30, of which 10 will be prioritized for SKY Perfect JSAT use. JSAT is aiming to both diversify its revenue sources beyond satellite communications and expand its work in defense and intelligence. Meanwhile, Planet has since been able to do similar deals with Germany [Payload]and Sweden [SpaceWar], making satellite constellation services a significant portion of its business.

New JMoD EO constellation will move into high gear

Early in 2025, the Ministry of Defense announced a major intelligence satellite procurement [JEO 5] through which it would contract to build and operate a new satellite constellation for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (衛星コンステレーションの整備・運営等事業). JMoD was aiming to avoid building and operating the constellation itself. Rather, it would use a private finance initiative (PFI) procurement mechanism. This means they would contract with a private commercial operator (or, more likely, a consortium backing a single-purpose corporation) to build, own, and operate the constellation and necessary ground station infrastructure. JMoD would have priority access to the capabilities but the private operator would also be able to sell imagery to other clients in order to recoup costs. JMoD also clearly wanted a domestic, sovereign capability; all satellites must be domestically produced (国産衛星) by domestic companies, though they allowed for non-domestic launch services. This type of PFI structure is not new; JMoD uses a similar structure for the Kirameki defense communications satellites and JMA’s weather satellites (Himawari) are operated by a similar Special Purpose Company (SPC), Geostationary Meteorological Satellite System Service Co., Ltd (GMSS), which is, in turn, backed by Mitsubishi HC Capital, , and Internet Initiative Japan (IIJ).

JMoD awarded the contract in December and everyone is invited! As expected, the winning bid is a consortium led by Mitsubishi Electric, but the consortium is broad, they are joined by Synspective, iQPS, Axelspace, SKY Perfect JSAT, Mitsui Bussan, and Mitsui & Co. Other than perhaps IHI and NEC, the consortium includes many of the major incumbent satellite manufacturers and New Space firms operating active satellite constellations in Japan.

JMoD is prioritizing high revisit cadence over Japan and surrounding regions. Once fully operational, they want persistent situational awareness with at least one satellite always having a shot at any location in the region. The consortium will also need to develop a dedicated ground segment (専用地上施設) secured for defense-related data handling. It’s a five year contract (through March 2031) so the consortium will have to hit the ground running.

Commercial space station race will begin taking shape

We are now only four years from the planned de-orbit of the International Space Station (ISS).

Several Japan firms have placed bets on one of the four commercial space station efforts aimed at succeeding the ISS, and some key tests are expected in 2026.

Trading company Mitsubishi Corporation (三菱商事株式会社) just increased its investment in Starlab Space, joined the Board of Directors, and became one of its biggest customers [Starlab Space] by pre-purchasing capacity on Starlab’s commercial space station. Starlab will not be launching in 2026, but it will face a Critical Design Review (CDR) and a full-scale mockup will be assembled in Houston at Johnson Space Center in order to test human factors design and operations.

The Axiom Space space station, backed by an investment from trading company Mitsui & Co (三井物産株式会社) is expected to continue manufacturing and integration of several modules this year with plans to launch its first module, a Payload Power Thermal Module (AxPPTM), to the ISS in 2027. After spending some time attacked to the ISS, it will detach in 2028 in order to rendezvous with habitat modules (AxH1 and AxH2), an Airlock module, and Research and Manufacturing Module and be ready for operation in 2030.

Axiom Space space station assembly process

In addition to the maiden launch of Sierra Space’s Dream Chaser spaceplane (see above), Sierra Space and Blue Origin are developing Orbital Reef as a future commercial space station. A pathfinder version of the inflatable space habitat modules known as Large Integrated Flexible Environment (LIFE) is expected to launch in late 2026. When the production version of the LIFE modules begin launching in 2027, they will be chained together to form the full Orbital Reef space station. As key investors, Japanese firms Kanematsu (兼松株式会社), MUFG Bank, and Tokio Marine & Nichido have a lot riding on this work. Kanematsu is also working with IHI Aerospace to develop a version of the Passive Docking System (PDS) [Sierra Space]for Dream Chaser and Orbital Reef. The PDS complies with the International Docking System Standard (IDSS) and has been successfully used on the HTV and HTV-X cargo vehicles used to supply the ISS.

The first commercial space station developed by Vast, Haven-1, had been expected to launch atop a SpaceX Falcon-9 rocket in May 2026. However, it was recently delayed to early 2027 [Vast]. The Vast effort does not have a Japanese investor, but Japan Manned Space Systems Corporation (JAMSS) is a payload partner and will leverage its extensive experience managing operations on the ISS Kibo research module to develop a scientific research equipment module that will fly on Haven-1. Vast also recently increased its commitment to Japan by opening a Japanese subsidiary in Dec 2025, appointing former astronaut Yamazaki Naoko [Vast] as its first general manager.

Finally, NASA is expected to issue a long-delayed RFP for the next phase of its Commercial LEO Destination (CLD) contracts. Four firms received Phase 1 contracts, and one or two of the above are likely to win Phase 2 with hundreds of millions of dollars at stake [Ars Technica].

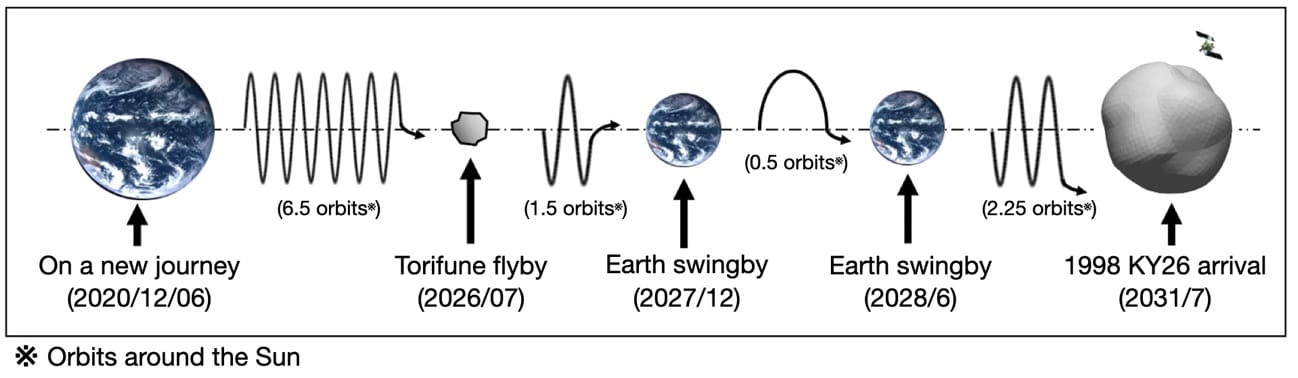

JAXA Hayabusa2 will attempt high speed flyby of Torifune asteroid

JAXA Hayabusa2 (はやぶさ2) is scheduled to perform a high-speed flyby of the asteroid (小惑星) 98943 Torifune (formerly 2001 CC21) on 5 July 2026. This is a rather extreme mission extension of the Hayabusa probe, which already visited Ryugu and sent samples back to Earth. Torifune is only 500m in size, and Hayabusa2 will approach Torifune at 5 km/sec and will shoot past in 0.1 seconds. After Torifune, Hayabusa2 will continue its journey, culminating in another asteroid visit to 1998 KY26 in 2031.

Illustration of Hayabusa2 journey to Torifune and 1998 KY26. Source: JAXA

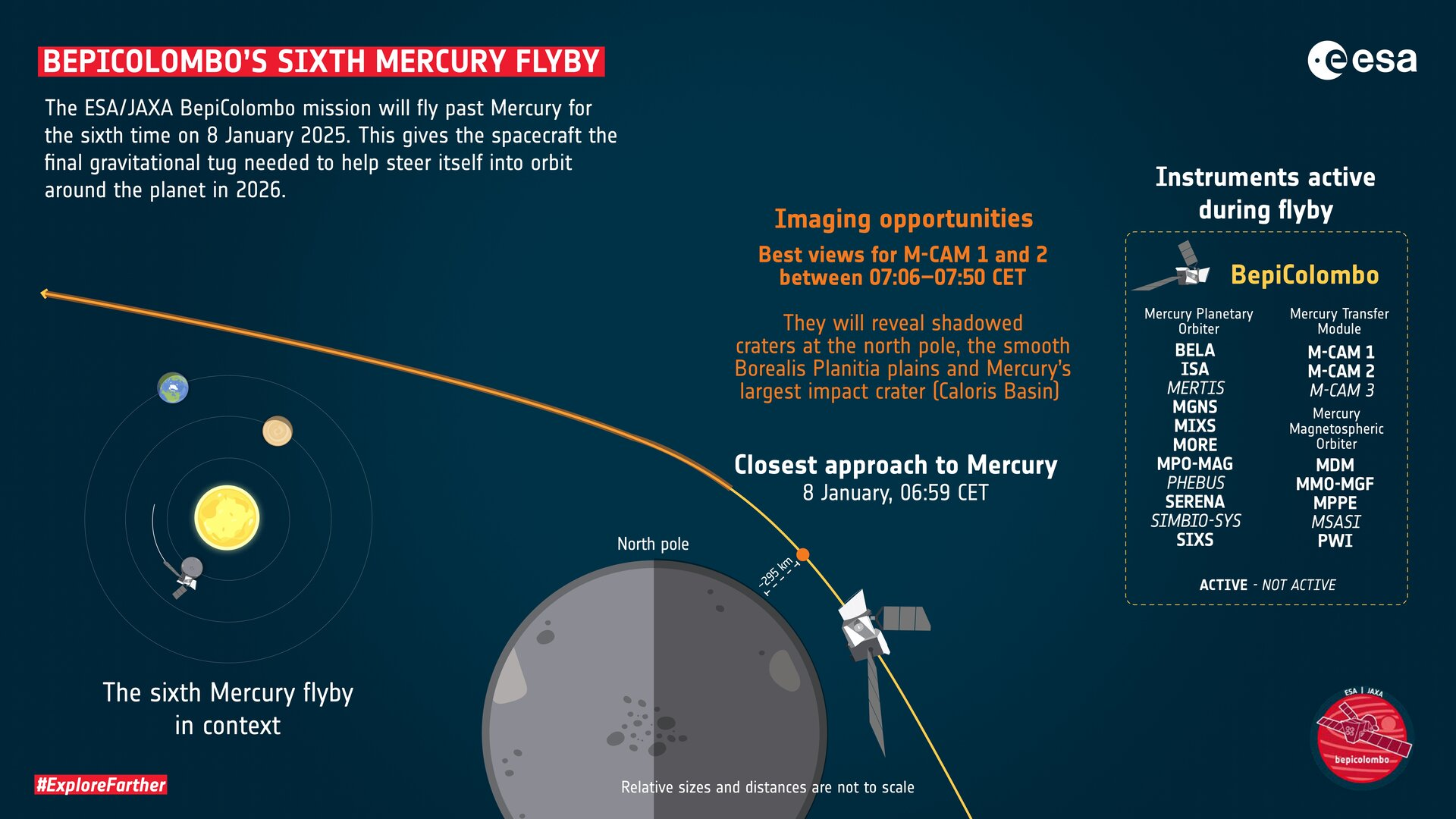

Joint ESA-JAXA BepiColombo mission will enter Mercury orbit

The ESA-JAXA BepiColumbo mission to Mercury is expected to complete its eight-year journey to Mercury in November 2026. Through six gravity-assist flybys of Earth, Venus, and Mercury, it has already collected good science data as well as tested its equipment. Once BepiColumbo enters orbit, it will separate into two orbiters. The ESA Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO) will study the planet’s surface and interior while JAXA’s Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter (MMO) will focus on the magnetosphere. They will both have to endure an astonishingly harsh environment at just a few tens of millions of kilometers from the Sun.

BepiColombo sixth flyby. Credit: ESA/BepiColombo/MTM

Japan will continue seeking domestic supply chain autonomy

Use of tariffs and other trade barriers by China and the United States over the past year have heightened concerns about supply chain autonomy and security for many countries. In addition, the temporary removal of Ukraine’s access to U.S. satellite intelligence in spring 2025 alarmed many of its allies and highlighted the degree to which they are dependent on these types of intelligence assets. The JSAT procurement of a satellite constellation from Planet Labs and the JMoD development of its own EO constellation described above are just two examples of efforts to procure and develop sovereign Earth observation satellite constellations. But sovereign control over rockets and satellites are only one facet of developing a secure, autonomous supply chain. Every material, component, and part has the potential to become a bottleneck if a single supplier or a single country controls the supply.

For Japan, these concerns are not new. For example, China previously cut off Japan’s access to rare earth minerals in 2010 over territorial disputes about islands claimed by both countries. Since then, Japan has quietly sought to develop its own rare earth mineral supply chain [NY Times], allocating US$1 billion in government support for developing a non-China supply chain in 2011. Sojitz (双日株式会社), a Japanese trading company, worked with the state-backed Japan Organization for Metals and Energy Security (JOGMEC 独立行政法人エネルギー・金属鉱物資源機構) to invest in Lynas, an Australian mining company. Lynas now mines rare earths in Australia and then refines them at their facility in Kuantan, Malaysia. The separated and refined ores are then shipped to Japan to be distributed by Sojitz. Another project led by JOGMEC seeks to develop a rare earth mine in Namibia. Other Japanese firms are developing technologies that avoid use of rare earths, decreasing demand.

In 2018, a Japanese research team discovered an estimated 16 million metric tons of rare earth elements in deep sea mud at 6,000m depth off the coast of Minamitorishima, a small island almost 2,000km southeast of Tokyo. Early in 2026, the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC 国立研究開発法人海洋研究開発機構) will use the deep-sea research ship Chikyuu to carry out exploratory mining of the mud [Nikkei Asia] to help guide development of the full-scale process slated to begin in 2027. Unlike the Australia mine, this mud has almost no radioactive or other toxic substances that add complexity and cost to the Malaysia refinery, and 16 million metric tons would potentially provide enough of some rare earth minerals for centuries of global supply.

But even after 15 years of steady investment, Japan has reduced its reliance on Chinese rare earth mineral imports from 90% to perhaps 60%, and the results remain far more expensive than Chinese sources of the same minerals. China repeated its rare earth mineral export ban again in late 2025, and it sent shockwaves across the industries that need these materials, from electric vehicles to robotics, sensors, and satellites.

And rare earth minerals are just one small part of the space industrial supply chain. Rocket engines and satellites require an enormous array of complex materials and components: radiation resistant solar cells and semiconductors, electric Hall-effect thrusters, specialized insulators, precision steel and alloy structures, power distribution units, magnetic sensors, radio transmitters/receivers, specialized batteries, precision optics, carbon fiber reinforced polymers, hydraulics and valves that can operate under extreme environments... I could go on, but you get the idea. Developing this domestic supply chain is an explicit goal of Japan’s Space Strategy Fund, and JAXA is awarding research funds to many firms that are trying to develop new materials and components. For example, Mitsubishi Electric has been funded to develop next generation solar cells and arrays and reduce the manufacturing cost.

Despite all of these efforts, developing a fully domestic supply chain for complex products like rockets, satellites, AI data centers, and EVs will be challenging for any single country. Strategic stockpiles, replacements, recycling, and domestic industrial capacity will only cover a portion of the critical materials needed, and Japan will doubtless need to rely on allies and trading partners to access the full array of materials and components that it needs.

Further, national resilience is built as much on human ideas as it is on materials and industrial capacity. Creative new ideas will come from people working with the best available tools. Japan has two historical templates for rapid acceleration of economic and technological progress: the Meiji revolution of the late 19th and early 20th century and the post-World War II period. In each case, Japan aggressively imported both the best technology and the best people and invested in education and human development of its citizens. In addition, both of these historical precedents involved radical restructuring of business and society, letting go of the legacy organizations and habits that no longer served the country. The Meiji revolutionaries discarded Tokugawa feudal socioeconomic structure and encouraged the development of countless new businesses and cultural habits. The post-WW II period began with dissolution of the major industrial conglomerates (zaibatsu) and removal of all senior executives by the U.S. Occupation authorities. Both events unleashed the creative and entrepreneurial potential of the Japanese people.

The Chikyuu research ship that will test deep sea rare earth mining processes. Source: JAMSTEC

Staffing, productivity, and demographics

Last year saw an estimated 667,500 births, the lowest number since records began in 1899 and significantly below government forecasts. Japan’s severe demographic crisis is not getting better. Meanwhile, Japan’s labor pay scale remains significant below that of comparable developed economies, and this is directly related to labor productivity that has lagged behind as well. 70% of construction companies in Japan report being unable to take on medium or large projects [Nikkei Asia] in 2026, primarily due to labor shortages. This affects every sector of society, including high tech sectors, like geospatial, AI, and space. Ideally, the way out of this will be a combination of rapid increases in productivity that enable every Japanese company to do more with fewer people, sustained wage increases that reflect the higher productivity, and either extension of the labor market to skilled immigrants or expansion to overseas locations. Infrastructure and manufacturing construction projects are particularly hard hit.

FOSS4G 2026 will be held in Hiroshima

There are dozens, if not a hundred or more geospatial technology conferences held around the world every year. Over the course of my career, one of the most consistently interesting has been the Free and Open Source for Geospatial (FOSS4G) conferences. FOSS4G is organized as both international and regional events under the aegis of Open Source Geospatial Foundation (OSGeo), often in collaboration with a regional chapter. There has been an international FOSS4G conference held almost every year since 2004. The event is organized in a different city each year, and the 2026 event will be held in Hiroshima 30 Aug - 4 Sept (English) (in Japanese) at the International Conference Center Hiroshima. This will be the first FOSS4G held Japan and it promises to be a significant event for anyone engaged in open source, open data, and open standards development. The calls for session proposals, academic papers, and half-day technical workshop proposals are now open with deadlines in March. Registration will open in late February with super-early bird tickets only ¥40,000 (~US $265). I plan on attending and look forward to seeing old friends and meeting new ones.

And that’s not all…

Above, I’ve outlined some of the high profile activity to watch for the coming year. There is a lot happening, but this list elides the array of manufacturers, service providers, and people that are behind the headlines, not to mention all of the downstream services that leverage EO and other geospatial data. Behind every one of the above projects is a complex human and material supply chain that is inventing and building the new technology that will be necessary to make them possible. For example, Eagle Industry is developing high performance seals for turbopumps that push liquid fuel into rocket engines; Composite Tailors creates carbon fiber reinforced polymers for space optical equipment; and Kurita Water Industries is working on water purification systems for a future lunar base. Once available, there is another downstream ecosystem of organizations that consume the services and infrastructure in order to provide new products and services that the headline projects will provide. It’s worth watching Degas Africa, Asia Air Survey, Kokusai Kougyou, Mierune, and Sagri many other geospatial data services companies in the coming year.

And developments in Japan will not happen in a vacuum. There are several planned missions to the moon, including China’s complex Chang’e 7 to the lunar south pole. SpaceX will be trying to get Starship V3 off the ground again; a successful series of launches will support future crewed missions to the moon and could again reduce launch costs. Artemis II is expected to launch as soon as February and carry a human crew around the moon and back. China is planning to launch a Xuntian, a large space telescope that will orbit alongside the Tiangong space station. NASA plans to launch the Nancy Grace Roman Telescope, a major new infrared telescope to explore the cosmos. India’s Gaganyaan-1, China’s Menzhou 1, and Boeing Starliner launches will test systems that are intended to become future crewed spacecraft.

The U.S.-China rivalry to reach the moon with a crewed spacecraft is headline news, but the global space industry is a complex ecosystem that mixes competition and cooperation. On the cooperation front, I am hopeful that ongoing discussions at UN COPUOS (Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space) will result in increased adoption of guidelines for reducing space debris as well as improved communication of orbital data that will reduce the chance of future collisions. Further, I think there are many more opportunities for Japan, India, the U.S., China, and the EU to cooperate on space exploration.

In July 1975, in the midst of the Cold War, the U.S. and the Soviet Union were able to launch and dock their rival spacecraft in the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project. It was an inspiring display of science and research cooperation. The ISS, CEOS, and weather data sharing have all demonstrated what is possible when many nations work together to accomplish what they could not do on their own, and we need more of this type of cooperation to manage our shared resources. Debris mitigation, orbital management, bandwidth sharing, lunar exploration, and disaster response are all areas in which the leading space-faring nations can work together, build shared understanding, and advance the frontiers of science and technology. And I think Japan occupies a unique position that could help catalyze such efforts.

The joint U.S.-USSR crew for the Apollo-Soyuz Test Mission in July 1975. Source: NASA

If you’ve made it this far, thank you for reading. Please be in touch via LinkedIn with any feedback, questions, comments, or requests for future topics. And if you have a friend or colleague that you think would enjoy JEO, please share it!

Until next time,

Robert

Evening snow;

people passing by

in silence.

– Kobayashi Issa (1763–1828) - translated by David LaSpina

夕雪や

人の通るも

だまりつつ

Yūyuki ya

hito no tōru mo

damaritsutsu