JEO 8 - Japanese Trading Companies and Orbital Real Estate

A monthly news roundup plus a deep dive on the Japanese trading companies and their investment in future commercial space stations.

Welcome to Japan Earth Observer (JEO), a free monthly newsletter with a news roundup and one in-depth article about the space, Earth observation and geospatial industries in Japan. In addition to a news roundup, in this edition I’m also going to write a bit about some of Japan’s trading companies and their investments in the next generation of commercial orbital real estate.

News & Announcements

💱 Contracts and Funding

- Astroscale UK signed a contract to provide its next generation docking plates to Xona [SatNews], developer of navigation satellite constellation for low Earth orbit (LEO)

- Astroscale has been awarded a patent for its innovative active debris removal architecture [SatNews]. U.S. Patent No. 12,234,043 B2 covers Astroscale’s new approach to debris removal which can cost effectively, flexibly, and safely deorbit multiple large objects. Under this approach, a “servicer” vehicle approaches a debris object, attaches to it, moves it to a lower orbit, transfers it to a “shepherd” vehicle, separates, and proceeds to another object. The shepherd vehicle either remains docked as it guides the object through reentry, or can perform a reentry insertion and then return to orbit for another object.

- Why does this matter? Patents represent a short-term monopoly during which time a firm can leverage the technology to build competitive advantage. If another firm wants to use Astroscale’s approach, they will have partner or license the technology from them.

Rendering of Astroscale servicer and shepherd spacecraft removing debris. Credit: Astroscale

- Mitsubishi Electric has been awarded funding from the JAXA Space Strategy Fund to develop domestic technology and a supply chain for radiation resistant solar cells, panels, and cover glass for future satellite solar arrays.

- Why does this matter? Satellite solar panels present engineering challenges not faced in terrestrial applications. They need to combine low weight, high photovoltaic energy conversion efficiency, and radiation resistance. The photovoltaic efficiency tends to decline due to damage from effects of space radiation, so resistance to degradation can have a big impact on the longevity of a satellite. PXP Corp, a firm that specializes in innovative photovoltaic materials such as perovskite and copper indium gallium selenide (CIGS), will be a key partner on the R&D effort. The six year project will research the feasibility of tandem perovskite/CIGS solar cells as well as develop radiation resistant cover glass.

- ICEYE Japan, the local subsidiary of Finnish ICEYE, has appointed Tsukahara Yasuhiro as its new CEO. Tsukahara was previously the COO of Japan Space Imaging (JSI) (日本スペースイメージング) and almost 30 years at Mitsubishi Corp. THE CEO role is a new one for the Finnish firm's Japan outpost. The previous head of the unit was the General Manager, Higashi Makoto (the former CEO of JSI).

- Why does this matter? ICEYE's business in Japan has been growing for several years and it likely has its chill eye on getting a piece of the Japan Space Strategy Fund action. Most recently ICEYE has teamed up with IHI to build a new 24-satellite SAR constellation in Japan, and they are already planning a domestic manufacturing facility to build it. It’s not clear to me that Japan needs a third domestic SAR constellation (the other two are iQPS and Synspective), but maybe there’s more demand than I think, and I suppose someone’s going to get paid to build and launch those satellites, so that’s probably good, right?

- SkyPerfect JSAT (スカパーJSAT) plans to triple its capital expenditures over the next three years [SatNews]. It's already invested about $489 million over the past three years, but plans to invest JPY 100 billion (~US $689 million) annually in 2025, 2026, and 2027. This includes investments upgrading its legacy direct-to-home satellite broadcast services, buying a Pelican constellation from Planet Labs, investing in Space Compass (a joint venture with NTT to build a GEO orbit optical data relay service in collaboration with iQPS, AxelSpace, and Synspective), and potentially making a contribution to the European IRIS2 constellation. JSAT will also be repositioning a satellite and is planning to launch three new ones in order to increase broadband access.

- First, in-flight WiFi provider, SES S.A. has signed an agreement to access the full Ku-band capacity of JSAT's Superbird-C2 in order to improve in-flight access over Asia. Superbird-C2 currently orbits at 144°E but will be repositioned to meet SES's needs. Demand for in-flight internet is increasing sharply as passenger numbers and expectations increase.

- Second, JSAT is planning to launch three new broadband communications satellites on SpaceX rockets in 2027 and 2028 in order to increase in-flight, maritime, defense, and disaster broadband capacity. Two of the birds will be so-called "flexible" satellites that will orbit in geostationary (GEO) orbit at 36,000 km and are capable of adjusting their coverage area, bandwidth, and communications frequency as needs change.

- Why does this matter? JSAT's legacy pay TV subscriber numbers continue to decline, so it has been moving aggressively to expand into Earth observation, satellite broadband, and other sectors. Its fiercest competitor will likely be SpaceX Starlink, which is already in use by the Japanese Coast Guard and Maritime Self-Defense Force and also has inked partnership agreements to provide satellite mobile phone services for customers of Japan's three largest mobile carriers: NTT Docomo, Softbank, and KDDI. The number four mobile carrier, Rakuten Mobile, will use AST SpaceMobile. Both Starlink and AST rely on constellations in low Earth orbit (LEO), where network latency is far lower than JSAT's GEO orbits. JSAT will have to run hard if it's going to go toe-to-toe with Starlink and AST.

- Lunar mission startup ispace and Indian space situational awareness (SSA) firm, Diganterra, have signed an agreement to collaborate on tracking objects in cislunar orbit. There a are a lot of lunar missions planned over the next few years. The moon is a lot smaller than the Earth, and its orbits are likely to become crowded more easily than the Earth orbits (which are already crowded). The two firms are anticipating future problems and planning ahead to build long-term safety and deconfliction infrastructure.

- Why does this matter? This new commercial partnership comes in the wake of the formalization of the JAXA-ISRO partnership to build and launch the Lunar Polar Exploration (LUPEX) mission in 2028 to search for lunar water. LUPEX has been under development for a while, but there has been a flurry of commercial and government partnership announcements this summer between Japan and India as well as Japan and Europe (see RAMSES mission to asteroid Apophis, below). With many NASA and NOAA earth science and planetary exploration missions under threat from the White House, I think this is more evidence of a rapid adjustment of priorities toward weaving collaborations with more reliable partners.

- ArkEdge Space has won a contract to test the new, high precision QZSS positioning signals [GPS World] on a network of next-generation Asia-Pacific tide monitoring buoys. ArkEdge Space designs, manufactures, and operates micro-satellites that can support IoT and maritime communications technology such as VHF Data Exchange System (VDES).

- Why does this matter? The QZSS satellite constellation augments the U.S. GPS navigation and positioning system in the Asia-Pacific region. The latest QZSS satellites support a new L6 signal called Multi-GNSS Advanced Orbit and Clock Augmentation for Precise Point Positioning (“MADOCA-PPP”). This new signal provides real-time, high-precision position augmentation - in other words, it enables receivers to have a much better measurement of exactly where they are. Starting in November 2025, the new buoys will measure and transmit real-time sea level data from across the Asia-Pacific. Real-time data on sea level will enable improved tsunami and storm surge monitoring. The Japanese QZSS constellation is already a generation ahead of the U.S. GPS constellation - which has been slow to modernize - and everyone in the Asia-Pacific benefits from this. The newest batch of QZSS satellites improves on this positioning augmentation and messaging services for disaster and other emergency scenarios.

- IHI Corporation is partnering with British infrared satellite firm, SatVu, to explore designing, building, and operating a high resolution thermal infrared satellite constellation. It's not a done deal yet, but if it moves forward, the satellites will likely be manufactured in Japan and will aim to support both national security and commercial applications.

- IHI (formerly Ishikawajima-Harima Heavy Industries 石川島播磨重工業) is a big industrial conglomerate of almost 30,000 employees with history stretching back to 1853. IHI built Japan's first steam-powered warship in 1866, the first jet engine in 1945, the Epsilon rocket used for sub-orbital research missions, and a range of other accomplishments. IHI's Aero Engine, Space & Defense group has been on a tear lately. IHI signed a similar agreement with ICEYE in May for a 24-satellite SAR constellation, and it also inked a deal with Surrey Satellite Technology (SSTI) just two days later. The SSTI deal will cover a range of Earth observation modes: optical, hyperspectral, radio frequency (RF), VDES, and infrared (IR). If all of these constellations move forward, IHI will become a one-stop-shop for intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) applications in Japan.

- Why does this matter? The SatVu and SSTI tie-ups are both being presented under the aegis of the Hiroshima Accord signed in 2023 between the UK and Japan to strengthen space and defense ties. But I think they provide further evidence of a broad push by several countries to build "sovereign" (domestically manufactured, operated and controlled) Earth observation and other national security capabilities in the wake of the perceived weakening of U.S. commitments to mutual defense, not to mention aggressive tariffs being assessed against allies.

- Astroscale has signed a launch agreement with NewSpace India Limited (NSIL) to launch the ISSA-J1 spacecraft to approach, diagnose, and inspect two large satellite debris objects in orbit. Astroscale is building this debris inspection spacecraft using a Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) grant from the Japanese government. Astroscale reviewed ten potential launch providers before settling on NSIL and the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV) for a dedicated launch from the Satish Dhawan Space Center in Spring 2027. The PSLV has had 60 successful launches and tends to be lower cost than other dedicated launch vehicles. In addition to the NSIL agreement, Astroscale has also recently signed MOUs with Indian firms Bellatrix and Digantara.

- Why does this matter? I think we can read this as part of an increased cadence of collaborative efforts between Japan and India in the wake of tariffs, insults, and other behavior from the United States.

- Rocket Lab has recently racked up a pile of launch contracts with Japanese entities:

- Synspective has signed a new contract with Rocket Lab for ten more dedicated launches of its StriX SAR satellites on the Electron rocket [Synspective], bringing the total to 21. Rocket Lab has already launched six StriX satellites and five more are queued up. Synspective has not outlined the schedule for the additional ten launches, but a key advantage of working with Rocket Lab is its track record for a flexible, reliable, and timely launch schedule. In addition, the Strix satellites have a particularly wide frame, which spurred Rocket Lab to build a custom "arrowhead" payload fairing to accommodate it.

- Not to be outdone, iQPS also signed a contract with Rocket Lab for three more dedicated launches of its QPS-SAR satellites starting in 2026 [Rocket Lab]. Electron rockets have already launched four iQPS satellites this year: QPS-SAR-9 to QPS-SAR-12 and another one is planned for November.

- And finally, JAXA bought two Electron launches for science and research payloads [Rocket Lab] that would have normally launched on the domestic Epsilon-S rocket. But that system has had two test failures over the past two years, setting back development.

- Japanese lunar exploration firm, ispace, has raised a pile more cash through an equity offering [Payload] in order to get back to the moon and have another shot at a successful landing. While it has a pretty good contract backlog and revenue is growing, it's burning through cash at a prodigious rate, clocking a net loss of ¥2.88 billion (~US $19.2 million) in the most recent quarter, double the losses over the same period last year.

- Why does this matter? The new cash from the equity sale should enable ispace to launch Mission 3 and and Mission 4 in 2027 and 2028 as well as cover operating costs in the meantime. The firm will sell 49 million new shares, of which 19.2 million will be a public offering and the remaining 30 million will be bought by Japanese institutional investors. With only 106 million shares outstanding at the beginning of October, another 49 million shares seems like a big dilution, and the share price fell to 475 yen after the deal closed on 21 Oct.

The ispace stock price over the past year; the big drop in June was after the June HAKUTO-2 crash.

🛰️ Technology and Infrastructure

-

The Hokkaido Spaceport and its operator Space Cotan are working with Firefly Aerospace to evaluate Hokkaido as a potential launch site [Asahi Shimbun] for its Alpha rocket. In addition to JAXA’s launch pads at Uchinoura and Tanegashima, several other spaceports are operating or under active development. TiSpace launched the first foreign rocket from Hokkaido in July, Sierra Space is planning to land space planes in Oita starting in 2027, and Space One is launching from Spaceport Kii near Kushimoto, Wakayama.

-

NTT Data, NTT InfraNet, SoftBank, Tokyo Gas Network, TEPCO Power Grid, and Earthbrain have developed a geospatial technology system to rapidly gather and integrate data about underground infrastructure.

- Why does this matter? Much of Japan's critical infrastructure was built out during its rapid economic development and urbanization following WW II. Significant portions of underground infrastructure have already exceeded planned lifetimes, and a mix of labor shortages and supply costs have extended replacement timelines to 100 years or more. Further, electricity, gas, water, and telecommunications are interwoven, making them complex to disentangle. The new approach organizes the data into a new 3D cubic format, called "spatial ID", that allows the spatial relationship of each infrastructure component to be visualized and managed.

-

EdgeCortix, a Japanese semiconductor startup, is designing new AI chips for satellites, robots, personal devices [Nikkei Asia], and other "edge" computing environments with stringent power usage requirements. NVIDIA is the big gorilla amongst AI chip makers, but their chips, while extremely capable, are expensive and consume a lot of power. Contemporary satellites are already being designed with on-board AI processors in order to reduce data transmission delays and energy consumption, and EdgeCortix wants to capture part of the nascent market. EdgeCortix's first mass-produced AI chip, Sakura-II, uses only 25% of the energy of the equivalent NVIDIA chip by minimizing expensive memory access operations during data processing. They already have an agreement with lunar lander startup, ispace, and they just landed a contract with the U.S. Defense Innovation Unit (DIU).

- Why does this matter? The DIU contract seems like a big deal; it's the first ever by a Japanese semiconductor firm. NVIDIA's sky-high revenue and profit growth can't possibly continue indefinitely, and I expect there will be a lot of innovative startups trying to figure out how to undercut NVIDIA on different combinations of price/performance and thereby capture part of their market. Will EdgeCortix be an example of Clayton Christiansen's innovator's dilemma for NVIDIA? They've raised $100 million in funding to figure it out.

-

ElevationSpace and ispace are going to collaborate on an attempt to return lunar samples [Payload]. ispace would develop the orbital transfer vehicle (OTV) and sample collection lander while ElevationSpace would leverage its experience building reentry capsules. If successful, it would be the first lunar sample return mission by Japan.

-

Honda and Astrobotic are partnering to develop an integrated energy system [Payload] to support a future lunar base. Astrobotic is building a LunaGrid power system and a vertical solar array technology (VSAT) in 10kW and 50kW configurations. However, to provide power through the long lunar night, it will need a storage system. Honda has developed a regenerative power cell that uses electricity to generate and store hydrogen from water. When the solar cells lack sunlight, the hydrogen is then used to generate electricity, creating water for the next cycle. The two companies will test their technology in a one-year simulation of solar illumination conditions for various potential locations on the lunar south pole and to optimize the solar array generation capacity against the fuel cell size. The testing will be carried out in the United States, but it is part of Honda's R&D initiative to extend its terrestrial products to space applications including its recent test launch of a prototype reusable rocket.

Artist rendering of Honda and Astrobotic fuel cell concept. Credit: Honda -

A team that includes Japanese firm Warpspace, the University of South Australia, and Adelaide-based RapidBeam will collaborate on development of a prototype next-generation optical satellite communications system. The system will be tested on the Australasian Optical Ground Station Network, a consortium led by the university. Warpspace's multiprotocol optical modem, HOCSAI, will be used to test space-to-ground optical (laser) communications. RapidBeam is a resident startup at the university and is developing an advanced ground station network. This is one of several recent announcements about both ground-to-orbit and inter-satellite optical communications initiatives.

- Why does this matter? With more satellites in orbit and Earth observations satellites, in particular, having greater resolution and capturing broader swaths of spectrum, there is a substantial need to increase orbit-to-ground bandwidth. This is driving both a proliferation of ground stations and a need to expand beyond radio communications to optical transmission. However, while supporting much higher bandwidth, optical transmissions require much greater precision and can be attenuated by clouds, fog, and other atmospheric conditions.

-

Astroscale and Australia's HEO have signed a three-year deal to extend their collaboration on space domain awareness to higher orbits [SatNews]. Astroscale develops orbital servicing and debris removal services, and HEO builds and operates cameras that find and monitor objects in orbit, a capability known as space domain awareness (SDA). The two firms are working together to find and characterize orbital objects, develop catalogs of candidate debris clients, and then model how to safely service or de-orbit the debris. The new agreement will extend their existing collaboration on low Earth orbit objects (LEO) to objects in geostationary transfer orbit (GTO) and geostationary Earth orbit (GEO). In addition to the HEO tie-up, Astroscale also has a related three-year contract to develop demonstration technology for the Japan Ministry of Defense (JMoD).

- Why does this matter? As the orbits become more crowded, debris removal is becoming a critical element of space sustainability. I like the metaphor that Astroscale is using: this is much like how traffic cameras (HEO's technology) and roadside assistance (Astroscale's specialty) help to keep highways clear and safe.

-

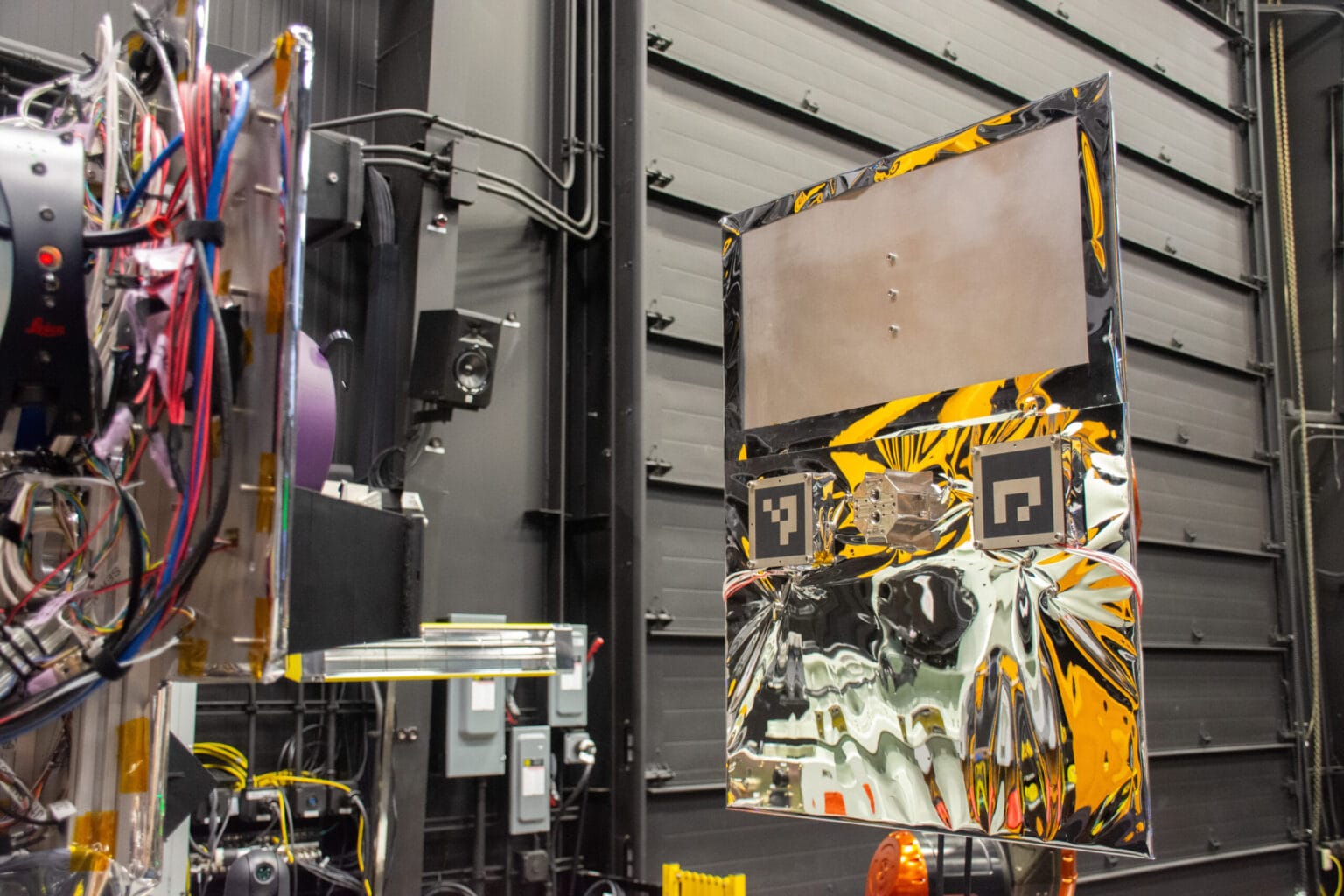

Astroscale has wrapped a test campaign at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center [NASA] in October. Goddard operates a Servicing Technology Center test facility that enables spacecraft operators to simulate orbital environments by attaching the spacecraft into a robotic motion platform that has a full 6 degrees of freedom. Astroscale's U.S. subsidiary worked with NASA to test various rendezvous and proximity operations (RPO) scenarios that will be necessary to carry out the APS-R mission, a first-of-its-kind hydrazine refueling operation contract awarded by the U.S. Space Force.

Robotic motion platforms for simulating RPO scenarios at the Servicing Technology Center (STC). Credit: NASA Goddard -

A research team led by professor Kunii Yasuharu at Chuo University has developed a small prototype robot, called RED [Nikkei Asia], that can use AI to operate autonomously as a collaborative group in order to explore harsh environments, such as the lunar surface. Working with Takenaka Engineering and a reinforcement learning AI research team led by Kawashima Hiroaki at Hyogo University, the team recently put the RED robot swarm through its paces at the JAXA test facility in Sagamihara.

A group of RED robots test collision avoidance. Credit: Kuroda Mann -

One of those Rocket Lab Electrons mentioned above successfully placed the Synspective Strix-7 SAR satellite [Space.com] in LEO (583 km) on 14 October. You might be wondering why they are called “Strix”. Strix is a genus of owls. Playing off this nomenclature, all of Rocket Lab’s launch missions for Synspective involve a play on “Owl”: "The Owl's Night Begins," "The Owl's Night Continues," "The Owl Spreads Its Wings," "Owl Night Long," "Owl For One, One For Owl," "Owl The Way Up" and now "Owl New World." While the 7th SAR satellite, this is the first of Synspective’s 3rd generation of its spacecraft, and is supposed to improve performance and reliability.

-

And another Electron rocket launched an iQPS SAR-14 satellite to a circular LEO (575km) orbit on 6 November (NZ time) [Space.com]. While labeled QPS-SAR-14, it’s actually the 13th iQPS (for some reason, their numbering scheme skipped from 12 to 14; superstition?). Having lost a couple in a failed launch in 2022 and three others that are no longer active, this brings their active constellation to 8 satellites on their way to a 36-satellite constellation. iQPS names its satellites after Shintō gods that appear in the earliest Japanese histories, the Kojiki (古事記) and the Nihon Shoki (日本書紀). This newest satellite is known as Yachihoko-I.

- Thus far, the iQPS satellite names have included: Amateru (天照神), Izanami (イザナミ or 伊弉冉尊), Izanagi (イザナギ or 伊邪那岐), Tsukuyomi (ツクヨミ or 月読), Susanoo (スサノヲ), Wadatsumi (海神 or 綿津見), Yamatsumi (大山津見神 or 大山祇神), Kushinada (くしなだひめ or 櫛名田比売), and now Yachihoko. (There was also a pathfinder satellite, called Tsukushi (筑紫島), an old name for the island of Kyushu where iQPS is based.). Yachihoko-no-Kami (八千矛神 or 八千戈神, lit. "God of Eight Thousand Spears") is a name used in the Kojiki by the Shintō god Ōkuninushi (オオクニヌシ or 大国主), the head of the Kunitsukami (国つ神 or 国津神), the gods who govern the earth, nation-building, and agriculture, among other domains, and live in the earth (tsuchi). Many of the myths told in the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki are about the various rows between the Kunitsukami and the Amatsukami (天津神, 天つ神) or gods of heaven.

- Yachihoko (or Ōkuninushi) is the god of nation-building. Rocket Lab has also named each of the iQPS missions based on the appropriate god, so this launch was called "The Nation God Navigates". Others have included: "The Lightning God Reigns", "The Sea God Sees", "The Mountain God Guards", "The Harvest Goddess Thrives".

🔭 Science

-

The National Institute of Information and Communications Technology (NICT 情報通信研究機構) has been awarded an R&D project to funded by the Japan Space Strategy Fund to develop and test quantum encryption key distribution (量子暗号鍵配布) to secure communication between satellites and ground stations. NICT aims to develop a small satellite that could be launched to low Earth orbit (LEO) in order to test quantum cryptographic technologies. NICT will collaborate with SkyPerfect JSAT (スカパーJSAT) on design and planning of the satellite control system. This is an extension of research work NICT has been leading to develop production-ready quantum encryption technology by 2030.

-

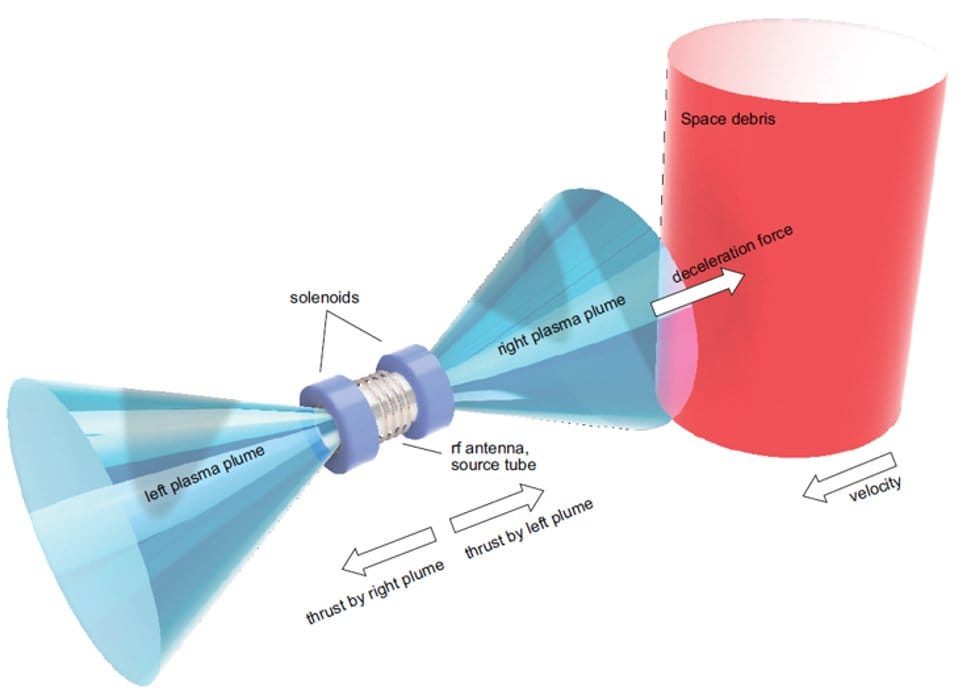

A Tohoku University researcher, Takahashi Kazunori, has developed an innovative approach to clearing debris [Space.com] without the risk of creating additional debris in the process; there is no need to make contact with the debris.

- Why does this matter? With both 10,000s of new satellites and more than 14,000 pieces of junk in low Earth orbit (LEO) ranging in size from bolts to rocket fairings, orbital debris is a rapidly growing problem. Startups like Astroscale are developing spacecraft equipped with docking plates and grappling arms in order to deorbit the largest pieces, but this won't address the vast majority of debris, which is small, tumbling, and moving at very high speed. Takahashi’s idea is to use a pair of ionized plasma engines (powered with argon or xenon) that push against each other in the opposite direction. The equal force from paired engines will cancel each other out (so the debris-clearing satellite will remain stable), but when one of the engines is directed at debris, it will gradually nudge it toward a deorbit trajectory. It's sort of like using an electric fan or a leaf blower to sweep your sidewalk. Pretty cool, right? The growing amount of space debris requires urgent solutions, and this is a creative one.

Diagram of the bi-directional plasma thruster concept for deorbiting space debris. Credit: Tohoku University

- Why does this matter? With both 10,000s of new satellites and more than 14,000 pieces of junk in low Earth orbit (LEO) ranging in size from bolts to rocket fairings, orbital debris is a rapidly growing problem. Startups like Astroscale are developing spacecraft equipped with docking plates and grappling arms in order to deorbit the largest pieces, but this won't address the vast majority of debris, which is small, tumbling, and moving at very high speed. Takahashi’s idea is to use a pair of ionized plasma engines (powered with argon or xenon) that push against each other in the opposite direction. The equal force from paired engines will cancel each other out (so the debris-clearing satellite will remain stable), but when one of the engines is directed at debris, it will gradually nudge it toward a deorbit trajectory. It's sort of like using an electric fan or a leaf blower to sweep your sidewalk. Pretty cool, right? The growing amount of space debris requires urgent solutions, and this is a creative one.

-

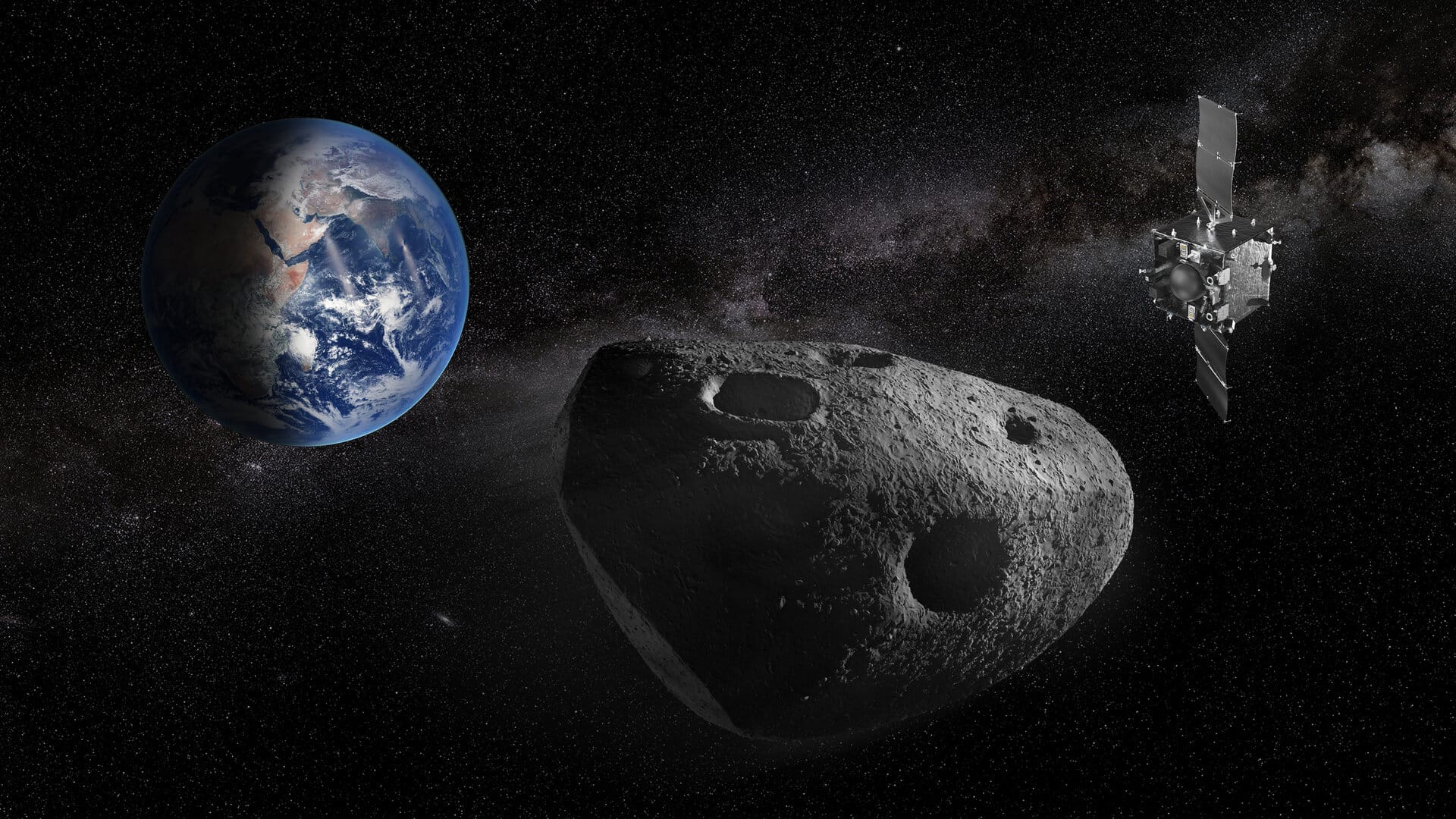

The plucky Hayabusa2 asteroid probe survived a fraught trip to asteroid Ryugu in 2018 and then sent back samples to Earth in 2020. The probe still had fuel left, though, so JAXA planned an extended mission that would take Hayabusa2, first to flyby asteroid 2001 CC21 and then to continue its journey and rendezvous with a much smaller asteroid, 1986 KY26, in 2031. However, new observations from the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope (ESO VLT) [Phys.org] suggest that 1986 KY26 is only one-third the size and is spinning much faster than expected. And by "smaller" and "faster", it is really small, only 11m in diameter, and much faster, spinning every 5.35 minutes.

- Why does this matter? This observation is going to make Hayabusa2's rendezvous interesting (we know very little about such small objects) and challenging.

Artist's impression of Hayabusa2 mission touching down on the surface of the asteroid 1998 KY26. Credit: ESO/M. Kornmesser

- Why does this matter? This observation is going to make Hayabusa2's rendezvous interesting (we know very little about such small objects) and challenging.

-

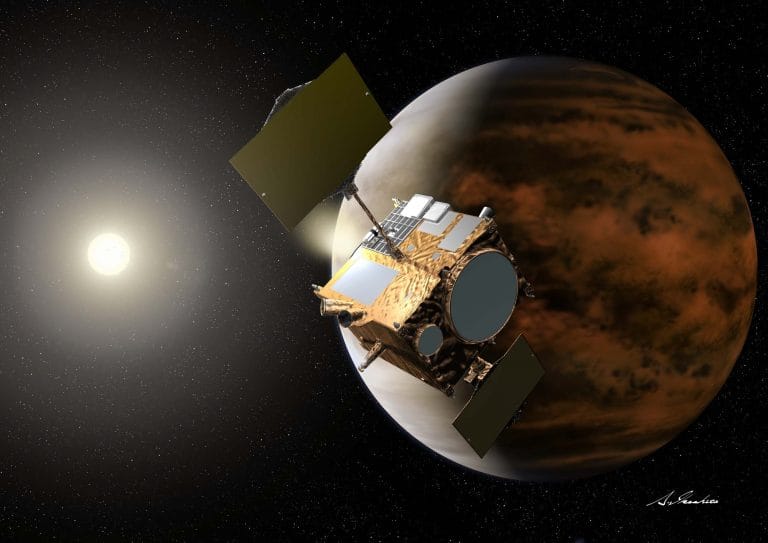

The Akatsuki (あかつき, 暁, "Dawn") probe to Venus has officially been declared ended [JAXA]. Akatsuki was sent to Venus (金星) in May 2010, but its main thruster failed the planned orbital insertion in December 2010. However, in 2015 JAXA was able to use its attitude thrusters to move it into a highly elliptical orbit around Venus and start its original science mission to study the climate and atmosphere.

- Why does this matter? Akatsuki's planned lifespan was only 4.5 years, and that much time had already elapsed when it entered orbit around Venus. However, all of its instruments were functioning, so JAXA laid out a two year observation plan. But it kept on functioning until April 2024, when JAXA lost contact. This was humanity’s only active mission to Venus, and recovery operations continued over the past year, but the mission was formally ended 18 Sept 2025. The $300 million mission has produced 178 scientific papers and counting. You can re-live Akatsuki’s exploits at its Twitter/X account.

Artist's impression of Akatsuki orbiting Venus. Credit: JAXA

- Why does this matter? Akatsuki's planned lifespan was only 4.5 years, and that much time had already elapsed when it entered orbit around Venus. However, all of its instruments were functioning, so JAXA laid out a two year observation plan. But it kept on functioning until April 2024, when JAXA lost contact. This was humanity’s only active mission to Venus, and recovery operations continued over the past year, but the mission was formally ended 18 Sept 2025. The $300 million mission has produced 178 scientific papers and counting. You can re-live Akatsuki’s exploits at its Twitter/X account.

🗺️ International Collaborations

- JAXA is planning to join the ESA Ramses mission to the Apophis asteroid [Kyodo News] planned for launch in April 2028 for rendezvous in April 2029, when it will pass within 32,000 km of the Earth. Apophis has attracted global interest from both scientific and planetary defense perspectives. If the 375m object collided with the Earth, it would be catastrophic. While there is no chance that it will collide with Earth on this transit, space agencies are keen to observe what will be the nearest approach of such a large object in observational history. Japan tentatively plans to provide solar panels and cameras as well as launch services on an H3 rocket. It will launch alongside JAXA’s own Destiny+ asteroid probe as it flies by Apophis on its way to a different asteroid. JAXA and ESA are already collaborating on Hera, another planetary defense mission to re-visit asteroid Dimorphos to investigate the NASA DART probe's impactor effects.

- In order for the Ramses mission to proceed, both ESA and JAXA need to have funding approved later this year, but this seems like another quiet effort by Japan to weave stronger ties with Europe, India, and other partners in the wake of abrupt changes in budget priorities imposed on NASA since the beginning of 2025.

- Why does this matter? NASA had planned to re-purpose its OSIRIS-Rex solar probe to also visit Apophis just after its Earth rendezvous in order to observe changes from the Earth transit, but the Trump administration has indicated they plan to cancel the mission, despite the fact that OSIRIS-Rex is already in space on a compatible trajectory following the end of its solar observation mission. China has also recently announced plans for an Apophis mission [SpaceNews].

Artist mockup of Ramses probe as the Apophis asteroid approaches Earth in 2029. Credit: ESA

📆 Asia-Pacific Conferences & Events

This newsletter is mostly focused on Japan, but I also like to highlight events across the Asia-Pacific region. Some upcoming conferences in 2025 include:

Jan 2026

- APACE 2026 - 27 - 29 Jan - Sarawak, Malaysia

- FOSS4G Asia 2026 - 21 - 25 Jan - Nashik, India

- State of the Map India - 24 Jan - Nashik, India

- Asia-Pacific Airshow & Exhibition (APACE) - 27-29 Jan - Sarawak, Malaysia

- International Space Industry Exhibition (ISIEX) - 28 - 30 Jan - Tokyo, Japan

February 2026

- OSM Mapper's Summit - 1 Feb - Osaka, Japan

- Space Summit 2026 @ Singapore Airshow - 7-8 Feb - Singapore

- National Space Science Symposium - 23 - 27 Feb - Shillong, India

- Spacetide/Keio University Special Workshop “Introduction to the Space Business” (「宇宙ビジネス入門」特別公開講座) - 22 Feb, 8 Mar, 22 Mar - Keio University Mita Campus, Minato, Tokyo, Japan

March 2026

- 65th JSASS Aviation Engine and Space Propulsion Conference - 9 - 11 Mar - Beppu, Oita, Japan

- Convergence India Expo - 23 - 25 Mar - New Delhi, India

- Space Technology Conference (STC) - 31 Mar - 1 Apr - Tashkent, Uzbekistan

- GEO Connect Asia 2026 - 31 Mar - 1 Apr - Singapore

- Committee on Earth Observation Satellites (CEOS) Disaster and Information Services Working Group Meetings - 16 - 20 Mar - Dehradun, Uttarakhand,India

Other recent videos

- JAXA 13th Exploration R&D funding solicitation briefing - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CgSPjB_bTXk

- JAXA Astronaut Onishi Return Press Conference - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7MVKGW9khSs

- JAXA Symposium 2025 “Beyond the Moon to an Infinite Universe” - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EgKRbB7Vhvo

- FOSS4G Japan 2025 - 12 Oct 2025

- Core Day - Room A - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kV6BV7BlLuM

- Core Day - Room B - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=45wB5wvbtAs

- Core Day - Room C - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uQHuziqXF5Q

- Spacetide and Keio University Graduate School of System Design and Management will hold a workshop, "An Introduction to the Space Business", at Keio University's Mita Campus in Feb and March 2026. The workshop, which will be free and include both on-line and in-person components, will be limited to 50 attendees. Applications are due Dec 15, 2025. This is a great opportunity for both professionals and students that are "space-curious" and looking for an introduction to opportunities, trends, and fundamentals of the industry.

Launches

- HTV-X launch - 25 Oct 2025

- JAXA (English) - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EBEq84QrSEA

- JAXA (Japanese) - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ljdP_M5k_-g&t=272s

- HTV-X ISS rendezvous and docking - 29 Oct 2025

- NASA (English) - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OXm8uc5OB70

- JAXA (Japanese) - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kvfZ7KGQLWo

- JAXA RAISE-4 launch - 14 Oct 2025

- Rocket Lab (English) - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cMP328yoUu4

- JAXA (Japanese) - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=REvfb0KvU_Y

Japanese Trading Companies and Orbital Real Estate

Over the past few months there have been a couple of major announcements from so-called “trading companies” making investments in space-related companies in North America and Europe. First, in late August, Ursa Space Systems, a private U.S. company specializing in geospatial data analysis with satellite imagery, announced an investment from Sumitomo Corporation, a Japanese trading company. The additional investment will help Ursa Space expand its operations to Asia.

Then in early October, Mitsubishi Corporation (三菱商事株式会社), another trading company (and one of many companies sharing the "Mitsubishi" moniker), announced they were increasing their investment stake in the Starlab Space [Nikkei Asia] effort to build a commercial space station to will succeed the ISS after it is deorbited in 2030.

If you follow the U.S. investment scene, you may have also heard of Japanese trading companies in another context: in 2020 five of these firms - Mitsubishi, Mitsui, Itochu, Sumitomo, and Marubeni - were the first investments Warren Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway had ever made in the Japanese economy. Berkshire initially bought a 5% stake in each of the five firms, but earlier this year increased its stake to almost 10% and then in late September increased its investment further in Mitsui and Mitsubishi. I doubt Buffett is making this decision based on the trading companies’ space investments, but it has drawn attention to these distinctly Japanese conglomerates, and I thought it might be interesting to take a closer look at both the trading companies, the various affiliated companies, and how they relate to the space industry.

What is a “Trading Company”?

The term “trading company” is a direct translation from the Japanese sōgō shōsha (総合商社); sōgō means “general” and shōsha means “trading company”. While they got their start as import/export businesses, they have expanded into international natural resources exploration, logistics, investment, and retail. They are extremely diverse companies with a stake in an extraordinary array of enterprises. In some respects they resemble large conglomerates like Berkshire Hathaway, but they have a number of key differences.

There are hundreds of shōsha in Japan, but there are five major ones that have a disproportionate impact: Mitsubishi, Mitsui, Itochu, Sumitomo, and Marubeni. With an aggregate market value at the end of FY2024 of ¥38 trillion (~US $260 billion) and ¥3.80 trillion (US $25.3 billion) in net profit, these are not small companies. Mitsubishi and Mitsui are the largest and have the longest history, but all five of the major shōsha are extremely diversified and own many entities both in Japan and globally. They often have significant investments in metals, mining, energy, and other commodities, but they also have investments in health care, retail, manufacturing, and components. As mentioned above, they are difficult to categorize and Moody's actually puts them in a category of their own. At a basic level, the shōsha are engaged in three activities: trading, investing, and operating businesses.

Trading: First, the trading business is similar to wholesaling or distribution and it's often international. The shōsha serve as intermediaries that buy something overseas and then sell it to a Japanese company or vice versa. Along the way, they provide support and consulting services as well as credit to either or both parties. I’ll go into a bit more detail about the origin story of the shōshas, but this trading activity was the historical core of the shōsha business.

Investing: Second, particularly over the past thirty years, shōsha have increasingly invested their own capital, particularly in businesses or sectors in which they have a lot of experience and deep knowledge. For example, Mitsui might invest capital in developing an iron ore mine in Australia and thereby gain access to the output of the mine, which it will then sell to a Japanese steelmaker.

Operating businesses: Third, for businesses in which they hold a controlling stake, the shōsha may also be a passive or active operator of the business. For example Itochu operates the Family Mart convenience store chain as well as having stakes in much of the supply and distribution chain that support Family Mart stores.

Research and information gathering: Finally, while it is not an explicit part of the revenue and profit of the shōsha, they serve as an intelligence and information agency for the network or family of companies with which they are associated. Their far-flung, global trading and investment activities plus their exposure to an extraordinarily diverse array of industries in Japan provide them with a remarkable network of information sources.

Many of the shōsha may be 150 year old companies, but they have a reputation for creative, challenging work and they pay 3-4x more than the average firm in Japan, so they tend to attract the best job candidates in the country. While the salary is attractive, they also have a reputation for giving young people a lot of hands-on experience and responsibility. In a Japanese work culture that is often focused on seniority as the mechanism for advancement, these are attractive places to work if you are young, bright, and ambitious.

| Trading Company | Market Cap (31 Mar 2025) | Revenue (FY2024) (Revenues) | Net Profit (FY2024) | Employees (Consolidated) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Itochu Corporation | ¥10.99 trillion | ¥14.72 trillion | ¥880.3 billion | 110,487 |

| Mitsubishi Corporation | ¥10.60 trillion | ¥18.62 trillion | ¥950.7 billion | 62,062 |

| Mitsui & Co. | ¥8.19 trillion | ¥14.66 trillion | ¥900.3 billion | 56,400 |

| Sumitomo Corporation | ¥4.11 trillion | ¥7.29 trillion | ¥561.9 billion | 83,327 |

| Marubeni Corporation | ¥3.97 trillion | ¥7.79 trillion | ¥503.0 billion | 51,834 |

| Total | ¥37.86 trillion | ¥63.08 trillion | ¥3,796.2 billion | 364,110 |

Where did the Trading Companies come from?

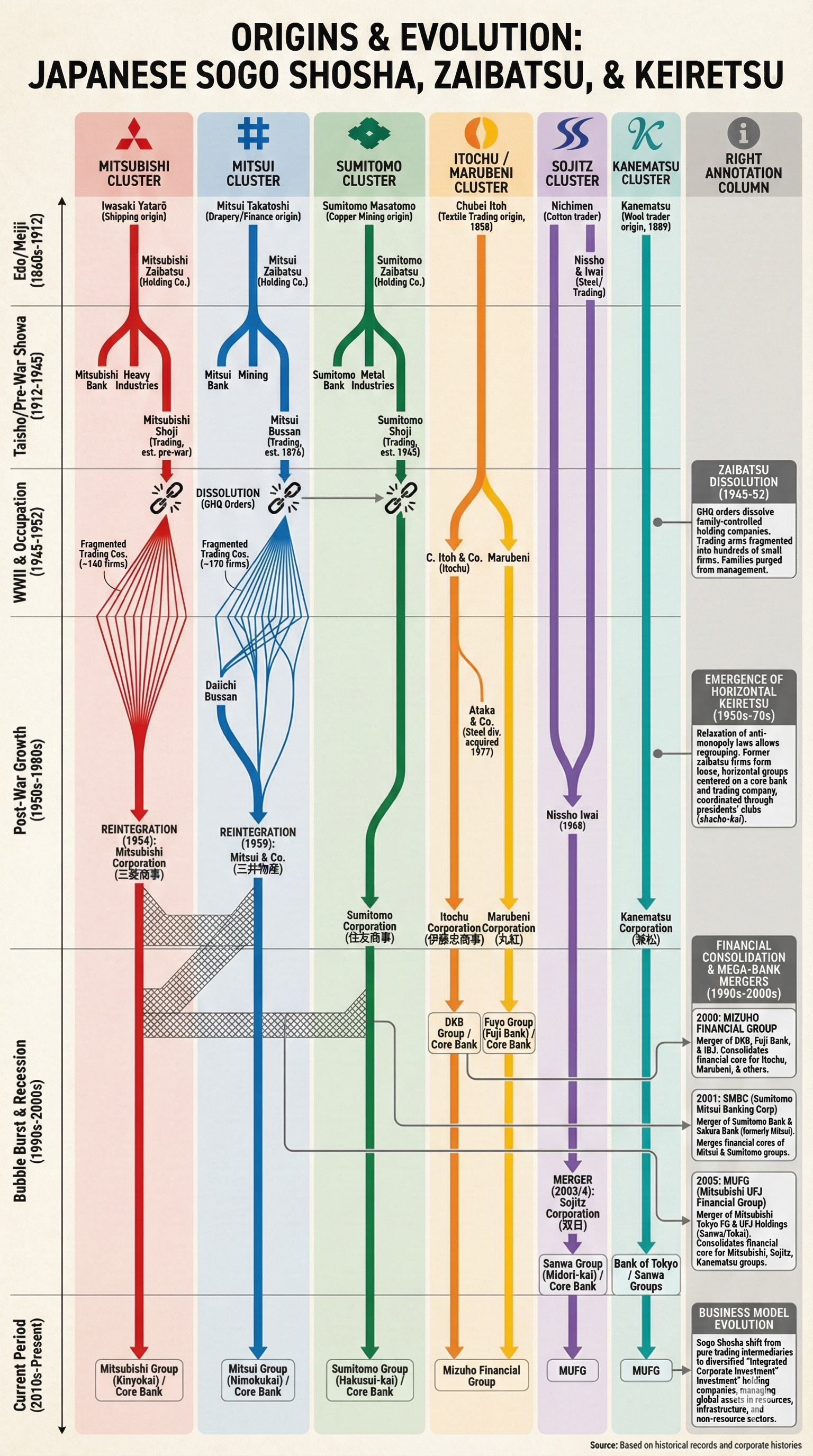

To understand the origin story of the shōsha, we need to look back to at least the Meiji Restoration of 1868, when Japan began a rapid industrialization process following more than 250 years of isolation under the Tokugawa shogunate. Japan's new leaders pursued an aggressive strategy of industrialization and adoption of systems and technology from the Western capitalist democracies, and the shōsha were born in this crucible.

The fall of the shogunate and the Meiji era of industrialization proved to be fertile ground for ambitious merchants and former samurai to create new businesses as well as older businesses to diversify in new ways. Through consolidation and acquisition, a few of these new companies grew into family-owned industrial conglomerates that often gained monopoly control of entire industries and became known as zaibatsu (財閥). Each zaibatsu was a holding company that owned several subsidiaries that were engaged in a range of industries, from shipping to manufacturing. Each zaibatsu also had a trading company or shōsha.

Japan had few natural resources of its own to support the industrialization process, and it was necessary for companies to purchase and import both raw materials and technology. Trading companies were set up to play this role. For example, early trading companies might purchase advanced machinery for textile manufacturing from the UK and Germany and cotton and raw materials from India and then sell it to the new Japanese textile companies getting off the ground. Alongside the machinery and commodities, they would also extend credit and provide training services.

Following Japan's surrender in August 1945, one of the first steps taken by the U.S. Occupation authorities was to force the breakup of the zaibatsu. About 2,000 senior executives were removed from their posts and banned from serving as executives in other firms; assets of the controlling families were seized, the holding companies were dissolved; and the interlocking directorships and cross-shareholding relationships were eliminated. Douglas MacArthur makes Lina Kahn look timid in comparison. This monopoly-busting and business leadership decapitation enabled both new firms and younger business leaders to fill the gaps as well as opening up new opportunities for the old components of the zaibatsu. Through the forced antitrust measures, the newly unfettered Japanese people were able to generate one of the most extraordinary examples of prolonged economic dynamism in human history. In 1950, people were still dying from starvation, and Japan’s per capita income was the same as Somalia and Ethiopia and 40% less than India. Japanese exports were weak. From 1951 to 1971, per capita income grew five-fold, and Japan was the second largest economy in the world by the late 1980s.

While the dissolution of the zaibatsu was an effective and powerful economic and social signal, the Korean War caused the U.S. Occupation to reconsider their trust-busting, and they reversed course in the 1950s. While the zaibatsu did not return, during the 1960s many of the historically companies gradually re-coalesced into loosely organized clusters of alliances that became known as keiretsu (系列). Each keiretsu typically has a major commercial bank, a trading company, and either a major manufacturing company or an insurance company as its core structural elements and then a flotilla of manufacturing and other operating companies. The whole structure was held together with a combination of cross-shareholding arrangements, presidents councils (社長会) for coordinating strategy, assigned directors, and intragroup financing. The core banks would provide capital for large-scale projects while trading companies would fund working capital of both customers and other keiretsu member companies. Over time, most Japanese companies became at least loosely affiliated with one of the keiretsu. This was not coercive. Rather, it was simply more convenient for a newly formed company to work with other members of a single keiretsu. This might start with a banking relationship or insurance relationship. Then, the bank would be in a position to learn more about your business and its needs and thereby be in a position to introduce your firm to other members of a keiretsu as new needs arose.

This keiretsu structure was very effective at supporting the period of rapid reindustrialization after WW II. However, because keiretsu tended to keep many transactions inside the group, there was a significant risk of becoming insular and risk-averse. The Japanese government recognized these drawbacks and over the past thirty years, a number of corporate governance reforms have forced the keiretsu to reduce the amount of cross-shareholding as well as bring in more independent directors. In addition, as the Japanese economy matured out of the initial textile, steel, and chemicals focus and expanded into consumer electronics and automobiles, new companies that were not affiliated with any of the keiretsu, like Toyota and Sony, began to grow rapidly and disintermediate the shōsha. Rather than sitting within a horizontal keiretsu, some of them developed their own vertically integrated hierarchy of supplier firms; Toyota is a paradigmatic example of this structure.

The combination of the yen appreciation that followed the 1985 Plaza Accord and the bursting of the real estate bubble in the early 1990s, the importance of the keiretsu and shōsha has gradually declined. More recently, technologies like the Internet have reduced some of the shōsha's information advantages as well. But human relationships and information networks are sticky and powerful, and the shōsha continue to provide key services to affiliated firms as well as invest in, operate, and provide services to a sprawling network of small- and mid-sized Japanese companies both inside and outside the old keiretsu networks. Further, over the past decade in particular, they have made significant improvements to their capital efficiency and return on equity, delivering much stronger results for shareholders. It is likely this combination of characteristics that has attracted Warren Buffett’s attention and investment.

I won’t go through the history of all five shōsha, but I think the history of a couple might be illustrative.

Sumitomo was first incorporated in 1919 as The Osaka North Harbour Company, but the broader business group can trace its roots back 400 years to the early 17th century, when a book and medicine shop was established in Kyoto by Sumitomo Masatomo, a former Buddhist monk. Masatomo's adopted son, Tomomichi, expanded the company into copper mining and refining. When Japan industrialized in the late 1800s, Sumitomo expanded its operations into heavy industry, real estate, chemicals, and manufacturing, becoming one of the huge zaibatsu conglomerates.

Following the dissolution of the zaibatsu, in late 1945 Sumitomo's real estate company renamed itself Nippon Engineering Co., restructured itself into a shōsha and shifted its business to import/export and product distribution, eventually becoming today's Sumitomo Corporation.

Sumitomo Corporation is part of the Sumitomo Group (住友グループ), a 630,000 employee keiretsu that includes Mazda Motors, NEC, Nippon Steel, Sumitomo Forestry, Sumitomo Mitsui Bank, and a slew of other companies. Management of the group is still guided by the "Founder's Precepts" written down by that former Buddhist monk in the 17th century.

Mitsubishi Groups’s (三菱グループ) origin story begins with Iwasaki Yataro (1835-1885), a young, low-ranking samurai in the Tosa clan of Kochi on the island of Shikoku, shifted from managing the Tosa clan’s Osaka trading operations to setting up his own shipping company, Tsukumo Shoukai (九十九商会), in 1870, by leasing three steamships from the Tosa clan. Iwasaki built a successful mail, cargo, and passenger shipping service. Meanwhile, the Meiji government had formed its own steamship business, the Japan National Mail Steamship Company (YJK) (日本国郵便蒸気船会社), using government-owned ships, government funds, and funds from wealthy merchant families. But there was a lot of infighting amongst the managers and they were unable to operate even intercoastal shipping.

In 1874 the Japanese government decided to launch a military invasion of Taiwan. The army was ready but Japan did not yet have a proper navy, so they tried to recruit YJK to transport the army, but YJK turned them down. Desperate to get on with an invasion, the government turned to Mitsubishi, which jumped at the chance. Iwasaki ended up taking over several government-owned ships and then leased them back to the government. The business grew quickly and Mitsubishi was soon able to force the American and British firms to abandon the Yokohama-Shanghai route. The firm was renamed Mitsubishi Shokai (三菱商会) in 1875 and then renamed again to Mitsubishi Mail Steamship Company (郵便気船三菱会社) later the same year.

By the 1880s there was general concern about Mitsubishi dominating the shipping business. The government and Mitsui (now the chief Mitsubishi rival) formed a new transportation company, Kyodo Unyu Kaisha (共同運輸会社), in July 1882 from three smaller firms: Tokyo Fuhansen Kaisha, Hokkaido Unyu Kaisha and Echu Fuhansen Kaisha. Kyodo Unyu kicked off a price war in January 1883. Over the next two years, the two companies competed fiercely, bringing both near bankruptcy. When Iwasaki Yataro died in 1885 and his brother, Iwasaki Yanosuke, took over, the government brokered a truce and forced the two firms to merge into Nippon Yusen (日本郵船), today’s NYK Line. The merged company now had a fleet of 58 steamships and expanded its operations to new ports in Asia as well as North America and Europe.

In parallel with building this shipping enterprise, Iwasaki was also engaged in developing other, related enterprises. He founded the first insurance company in Japan: Tokyo Marine Insurance (東京海上保険) in August 1879. But shipbuilding would become his more significant venture. The shipbuilding thread of his story begins in 1857, when the Tokugawa Shogunate (which had recently been shocked out of its complacency by Commodore Perry’s steam-powered warships showing up in Uraga Harbor in 1853) invited a group of Dutch engineers to help build a modern foundry and shipyard, Nagasaki Yotetsusho (長崎鎔鉄所). After the 1868 Meiji Restoration, the new Meiji government took over, completing the first dry dock in 1879. Iwasaki leased the Nagasaki shipyard from the government in 1884 and then bought it outright in 1887. After adding docks in Yokohama and Shimonoseki over the next forty years, in 1934 it was formally named Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI) (三菱重工業株式会社), becoming the largest private firm in Japan and cranking out ships, heavy machinery, airplanes and railway cars through the end of WW II.

Like the other zaibatsu, by WW II MHI was just one of several Mitsubishi companies. Iwasaki Yanosuke ran the company until 1893, when Iwasaki Yataro’s son, Iwasaki Hisaya, took over as president. Yanosuke had purchased copper, coal and other mines. When Hisaya took over, he proceeded to establish divisions for banking, real estate, marketing, and administration, alongside the existing mining, shipping, and shipbuilding businesses. He bought the Kobe Paper Mill (now Mitsubishi Paper Mills), and he invested in the founding of the Kirin Brewery. Hisaya was succeeded by Yanosuke’s son Koyata in 1916. Koyata changed the structure from divisions within one large firm to separate, semiautonomous companies in each sector. He also added new enterprises in machinery, chemicals, and electrical equipment. Mitsubishi Electric (三菱電機株式会社) was spun out of MHI (then Mitsubishi Shipbuilding) in 1921. Mitsubishi Shouji (三菱商事) was the trading company that handled import and export.

Under the U.S. Occupation the Mitsubishi Headquarters (三菱本社) was closed on 30 September 1946 and many of the Mitsubishi firms were split into smaller organizations. MHI was subdivided into three separate regional equipment manufacturing companies. Mitsubishi Shoji, the trading company, was broken up into 139 separate trading companies. Many of the Mitsubishi companies were encouraged to abandon the Mitsubishi name.

With the end of the Occupation and the outbreak of the Korean War, many of the legal restrictions were removed, and the Mitsubishi Group, like the other former zaibatsu, gradually re-formed around a core banking group, a trading company, and a major manufacturer. While never returning to the pre-war fully integrated structure, the related Mitsubishi companies reinstated a level of coordination and mutual support as autonomous, independent firms.

Many of the various subdivided trading companies re-formed into Mitsubishi Corporation. The restored trading company’s operations began to shift away from the mere importing and exporting of goods in the 1960s. Starting with an investment in a liquefied natural gas field in Brunei in 1968, Mitsubishi rapidly moved towards investing directly in projects and companies overseas, rather than simply trading commodities and products.

Today, the Mitsubishi shōsha holds interests in numerous large energy, mining, chemical, and infrastructure projects abroad, which generate the bulk of the company's revenue. It also operates consumer-facing businesses, including a 50% share in the convenience store chain Lawson, along with other ventures in finance, healthcare, food, and apparel, both in Japan and overseas. In recent years, Mitsubishi has also been active in investing in technology start-ups and clean energy projects.

An attempt to get Google Gemini to generate a diagram of trading company history.; Source: Google Gemini and online document.

Building Japan’s Space Industry

Following its reconsolidation from the three regional companies in 1964, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI) returned to cranking out ships, trains, machinery, and cars. Further, building on its experience building jet fighters and helicopters, in the 1970s MHI also entered the rocket business, building Japan's first liquid-fueled rocket, the N-I rocket based on the U.S. Thor-Delta launch vehicle and an MHI-designed LE-3 engine on the second stage. MHI has since remained the leading manufacturer on all of Japan's flagship launch vehicles, building the N-I, N-II, H-I, H-II, H-IIA, H-IIB, and H3. MHI also manufactures a significant portion of the HTV and HTV-X cargo spacecraft that ferry supplies to the ISS and built some components of the Kibo module on the ISS. Meanwhile, Mitsubishi Electric has built a substantial business designing and manufacturing satellites and satellite components as well as contributing to spacecraft such as HTV and HTV-X.

Below, I have tried to summarize the areas in which some of the keiretsu networks contribute to the launch, satellite, and geospatial ecosystems.

Mitsubishi Group (三菱グループ)

While the Mitsubishi Group has retained its original name and identity, the current group is actually the result of a series of mergers in the early 2000s. The Sanwa Group was led by Sanwa Bank (三和銀行) and had two trading companies: Nissho Iwai (日商岩井) and Nichimen (ニチメン). Following the stock market and real estate crash of the 1990s, Sanwa was loaded with bad debts and it merged with Tokai Bank and Toyo Trust to form UFJ Holdings (UFJホールディングス). Then UFJ Holdings merged with Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi to form Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, the current financial anchor of the Mitsubishi Group. Nissho Iwai and Nichimen merged in 2004 to form Sojitz Corporation (双日). While Sojitz and Mitsubishi Corp (the original Mitsubishi shōsha) share the same MUFG Bank, they remain competitors and Sojitz continues to be affiliated with the old Sanwa Group. I’ll treat Sojitz as if it is part of a separate Sanwa Group below.

| Company (English) | Company (Japanese) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group (MUFG) | 株式会社三菱UFJフィナンシャル・グループ | largest financial institution in Japan; operates a space innovation office; investor in many space and geospatial startups; offers eMAXIS Neo Space Development fund to enable retail investors to track global space economy firms |

| Mitsubishi Corporation | 三菱商事株式会社 | core trading company in Mitsubishi Group; investor in Starlab Space, Japan Space Imaging (JSI), PASCO |

| Mitsubishi Heavy Industries | 三菱重工業株式会社 | anchor manufacturer in Mitsubishi group; prime contractor and lead manufacturer of liquid-fuel rockets, rocket engines, and HTV cargo spacecraft; assembled ISS Kibo research module; propulsion and reaction control systems for satellites; rocket launch services |

| Mitsubishi Electric | 三菱電機株式会社 | major manufacturing and satellite systems integrator including communications, Earth observation, navigation, and scientific research; DS2000 satellite bus; satellite components; tracking and ground control systems; optical and radio telescopes |

| Mitsubishi HC Capital Inc. (MHC) | 三菱HCキャピタル株式会社 | formerly Mitsubishi UFJ Lease & Finance; owned by MUFG and Mitsubishi Corp; leads the private finance initiative (PFI), GMSS that operates Himawari weather satellites; co-invests with MUFG in space startups; financing for the transport and logistics of satellite and rocket components; leasing services for sensors and measurement devices |

| Mitsubishi Precision (MPC) | 三菱プレシジョン株式会社 | satellite attitude control systes; radio and inertial navigation sensors (RINA); subsidiary of MHI, MELCO, and MUFG |

| Mitsubishi Research Institute (MRI) | 株式会社三菱総合研究所 | space business research and consulting; space policy research; satellite data processing; satellite-based monitoring and surveillance; maritime logistics; disaster impact assessment; investor in New Space Intelligence (NSI) |

| Mitsubishi Cable Industries | 三菱電線工業株式会社 | rubber- and resin-based sealing parts (O-rings) for extreme environments; materials research; wholly owned subsidiary of Mitsubishi Materials |

| Mitsubishi Materials Corporation (MMC) | 三菱マテリアル株式会社 | specialty metal components and alloys used in rocket engines and launch vehicles, thermal protection systems; electronic components and circuits for satellites and ground stations; specialized tooling |

| NYK Line | 日本郵船株式会社 | developing sea-based rocket recovery ships |

| Tokio Marine Holdings | 東京海上ホールディングス株式会社 | launch and spacecraft insurance; investor in Sierra Space |

| Japan Space Imaging (JSI) * | 日本スペースイメージング株式会社 | distributes high resolution imagery from Japanese, U.S. and other commercial Earth observation satellites |

* JSI was established by Mitsubishi Corp to distribute high-resolution imagery, but Hitachi became the majority shareholder in 2013 and it is now jointly operated by Mitsubishi, Hitachi, and NEC Corporation.

Sumitomo Group (住友グループ)

| Company (English) | Company (Japanese) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sumitomo Corporation | 住友商事株式会社 | anchor trading company in Sumitomo Group; trading in satellite components and ground stations; investor in SpinLaunch, Synspective (SAR), Ursa Space Systems, and HawkEye 360 (RF) |

| Sumitomo Precision Products (SPP) | 住友商事株式会社 | high-precision gyroscopes for domestic rockets; acquired by Sumitomo Corp in 2023 |

| NEC Corporation | 日本電気 株式会社 | satellite manufacturing, satellite components, ground systems, services; investor in Japan Space Imaging (JSI) |

| NEC Space Technologies | NECスペーステクノロジー | payload, telecommunications, power control, data handling, attitude control, telemetry, and thermal control components for satellites and rockets; began as a joint venture by NEC (60%) and Toshiba (40%) called NEC Toshiba Space Systems Ltd. (NTSpace); NEC acquired Toshiba's shares in 2015 |

| Kaneka Corporation | 株式会社カネカ | films, cables, insulation for satellites; spun off from Kanegafuchi Spinning Co. in 1949 |

| MS&AD Insurance Group* | MS&ADインシュアランスグループホールディングス株式会社 * | spacecraft insurance and lunar insurance |

| Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation (SMBC) ** | 三井住友銀行 ** | financing for ground stations, spaceports, space logistics supply chains, and hyperscale data centers; investor in Interstellar Technologies and Space BD |

| Japan Aviation Electronics Industry (JAE) [historical] *** | 日本航空電子工業株式会社 *** | inertial measurement units (IMU) for rockets; accelerometers; magnetometers |

* MS&AD Insurance Group is the result of several mergers and is now associated with both the Sumitomo and Mitsui Groups.

** SMBC is the result of several mergers and is now associated with both the Sumitomo and Mitsui Groups.

*** NEC sold 33% share to Kyocera in Oct 2025, so JAE is no longer part of Sumitomo keiretsu; NEC Corp Retirement Trust still owns ~20% of the shares.

Mitsui Group (三井グループ)

| Company (English) | Company (Japanese) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Mitsui & Co (trading company) | 三井物産株式会社 | anchor trading company in Mitsui Group; investor in Axiom as ISS successor, Spire Global, Mitsui Bussan Aerospace, and Interstellar Technologies Inc. (IST) |

| Mitsui Bussan Aerospace | 三井物産エアロスペース株式会社 | specialized trading company for aerospace, defense, and space; satellite manufacturing, satellite development services, ground station services, satellite deployment services for Kibo; subsidiary of Mitsui & Co. |

| Japan LEO Shachu | 株式会社日本低軌道社中 | R&D on autonomous module and cargo resupply system technologies; design for next gen research module (successor to Kibo on ISS) and HTV-XC next gen cargo vessel; subsidiary of Mitsui & Co. |

| Toray Advanced Composites | 東レ・アドバンスド・コンポジット | carbon fiber, synthetic resin, advanced composite materials, fairings, heat sinks, and satellite structures; founded as TenCate Advanced Composites in 1972; acquired by Toray Industries (東レ株式会社) in 2018; Toray Industries was est. in 1926 as Toyo Rayon Co., Ltd. by Mitsui Bussan (the trading company that became Mitsui & Co.) |

| MS&AD Insurance Group* | MS&ADインシュアランスグループホールディングス株式会社 * | spacecraft insurance and lunar insurance |

| Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation (SMBC) ** | 三井住友銀行 ** | financing for ground stations, spaceports, space logistics supply chains, and hyperscale data centers; investor in Interstellar Technologies and Space BD |

* MS&AD Insurance Group is the result of several mergers and is now associated with both the Sumitomo and Mitsui Groups.

** SMBC is the result of several mergers and is now associated with both the Sumitomo and Mitsui Groups

DKB Group, Fuyo Group, and Mizuho

The current Mizuho Financial Group is the result of a series of mergers in the 1970s and 2000s. In 1971, Dai-ichi Bank (第一銀行) and Nippon Kangyo Bank (日本勧業銀行) merged to form Dai-ichi Kangyo Bank (第一勧業銀行), becoming the largest bank in Japan as well as the new central bank for the largest keiretsu at the time: DKB Group. The collapse of the asset bubble in the 1990s exposed mismanagement and corruption at Dai-ichi Kangyo Bank. In 2002 DKB merged with Fuji Bank and the Industrial Bank of Japan to form Mizuho Financial Group ('mizuho' (瑞穂) literally means ‘abundant rice’ but figuratively means 'harvest'). The greatly enlarged Mizuho is an investor in PASCO, SPACE ONE, and many other space and geospatial enterprises.

Despite the massive merger of DKB, Fuji Bank, and IBJ, rather than forming a new, enlarged keiretsu, the Fuji and DKB Groups continue to operate independently. Fuji Bank had led its own keiretsu, Fuyo Group (芙蓉グループ), that included Hitachi, Nissan, Canon, Showa Denko, and othersl, many of which continue to coordinate within the group. DKB also had a large keiretsu that included Kawasaki Heavy Industries and the Itochu shosha.

The DKB and Fuyo Groups also share another thread of common history. The anchor trading houses of each, Marubeni and Itochu, respectively, were founded by Itoh Chubei, a Kansai merchant who started a linen trading business in 1858. Due to a serious recession in 1921, the trading business was split into two parts: Marubeni and Itochu. However, in 1941, during WW II, the two trading houses were forced to recombine to form Sanko (三興株式会社), later renamed to Daiken (大建産業) when merging with two other companies in 1944. Then, in 1949, under the U.S. Occupation, Daiken was re-separated into the current Itochu and Marubeni. Post-war Marubeni (now part of the Fuyo Group) was initially mostly a textile trading firm, but it merged with the Takashimaya-Iida trading company in 1955 and diversified into retail, machinery, metals and chemicals in subsequent years. Itochu similarly diversified as part of the DKB Group, expanding from textiles to machinery, minerals, energy, chemicals, food processing, and retail.

Fuyo Group (芙蓉グループ)

The Fuyo Group formed after WW II from the former Yasuda, Asano, and Okura zaibatsu. Fuji Bank was the anchor financial institution but is now part of Mizuho. The Fuyo Group (“fuyo” means “hibiscus” and is also an alternative name for Mount Fuji, the namesake for Fuji Bank) continues to function separately with member company presidents gathering regularly in Fuyo-kai meetings. It includes the following firms operating in geospatial- and space-related industries:

| Company (English) | Company (Japanese) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Marubeni | 丸紅株式会社 | anchor trading company in the Fuyo Group; investor in D-Orbit (Italian space logistics firm) Orbit Fab (U.S. satellite refueling and storage); Interstellar (small launch vehicles); serve as the Japanese representative for several U.S. and European satellite components and ground station equipment manufacturers; founding member of Spaceport Japan Association |

| Sompo Japan Insurance | 損害保険ジャパン | formerly Yasuda Fire & Marine; wholly owned subsidiary of Sompo Holdings; rocket launch and satellite insurance to Mitsubishi, NEC, and JAXA; satellite methane emission detection and disaster response used in insurance business |

| Marubeni Aerospace Corporation (MAC) | 丸紅エアロスペース株式会社 | wholly owned subsidiary of Marubeni; most of aerospace work from 1998 Okura Aerospace Co acquisition; imports sensors from L3Harris for Himawari weather satellites as well as GOSAT-2; imports satellite buses, gyroscopes, and reaction wheels from Honeywell |

| Hitachi | 株式会社日立製作所 | historically part of the Fuyo Group, but increasingly works with other keiretsu; majority shareholder in Japan Space Imaging (JSI) (originally created by Mitsubishi); asset management software uses drone and satellite imagery; manufactures ground control systems and mission management software; space cybersecurity; joint venture GE Hitachi Nuclear Energy develops small modular nuclear reactors |

| Canon Electronics | キヤノン電子株式会社 | Canon Inc. (parent company) is part of Fuyo Group but operates independently in many respects; builds and operates high-resolution, low-cost microsatellites that put an EOS 5D or EOS R5 camera system into orbit; optical sensors and actuators; maritime situational awareness and disaster prevention services; investor in SPACE ONE and Marble Visions |

| Fujitsu | 富士通株式会社 | lead technology and ICT provider for the Fuyo Group as well as Mizuho; joint research with JAXA and Nagoya University on space weather forecasting; digital twin of the ISS Kibo module; simulations for satellite design; software to optimize orbits and ground station communication; digital twins; quantum computing for satellite material science; operates a Space Data Frontiers Research Center |

| OKI Electric Cable | 沖電線株式会社 | wholly-owned subsidiary of OKI Electric Group; high performance cabling and flexible printed circuits (FPCs) for satellites |

| RICOH | 株式会社リコー | a space-hardened, compact spherical camera used on ISS and HTV-X perovskite solar cells used on JAXA's HTV-X cargo vehicle; high resolution vehicle-mounted cameras for mapping; 3D digital twins |

| Resonac | 株式会社レゾナック | Showa Denko merged with Hitachi Chemical in 2023 and rebranded as Resonac; semiconductor materials and substrates; has an MOU with Axiom Space to continue its on-orbit research currently done on the ISS |

DKB Group (第一勧銀グループ)

DKB Group did not arise from a large Meiji era zaibatsu. Rather, it emerged in 1971 from the merger of three smaller lineages. Dai-ichi Bank was the core bank of the Shibusawa network founded by Shibusawa Eiichi (渋沢 栄一) in 1873. Nippon Kangyo Bank (NKB) was a former state-owned "special bank" focused on agriculture and regional industry. The industrial components came from the smaller Furukawa zaibatsu, including Furukawa Electric, Fuji Electric, and Fujitsu. The heavy industry component came from the smaller Kawasaki zaibatsu, which included Kawasaki Heavy Industries and Kawasaki Steel. The DKB Group combined the two banks and the Furukawa, Kawasaki, and Shibusawa industrial lineages into a new network. While the financial unit is now part of Mizuho, the DKB Group continues to function separately with member presidents regularly attending Sankin-kai (三金会) meetings. It includes the following firms operating in geospatial- and space-related industries:

| Company (English) | Company (Japanese) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Itochu Corporation | 伊藤忠商事株式会社 | historic shosha that anchored DKB Group; has an Aerospace and Mobility Division; investor in PASCO, Infostellar, ZeroAvia, Killic Aerospace, and Wingcopter; has long relationships with major defense and aerospace contractors like Boeing, Lockheed Martin, and Raytheon |

| Kawasaki Heavy Industries (KHI) | 川崎重工業株式会社 | rocket payload fairings; payload attachment fittings (PAF); Kibo module, satellites; H2 launch complex |

| Nihon Hikoki (NIPPI) | 日本飛行機株式会社 | satellite components and structural components for rockets and probes; developed components of the Lambda series rockets beginning in 1963; acquired by Kawasaki Heavy Industries in 2002 |

| Shimizu Corporation | 清水建設株式会社 | spaceport engineering and construction, propellant tanks, satellite data analytics; R&D on habitation modules; investor in SPACE ONE |

| SKY Perfect JSAT Holdings | 株式会社スカイパーJSAT(ジェイサット)ホールディングス スカパーJSAT(ジェイサット)株式会社 | satellite broadcast and communications; partnerships with KSAT (Kongsberg), Hawkeye 360, Planet Labs, and Taiwan CNS; broadcasts/operations in Indonesia, Vietnam, Philippines, Qatar; contract for dedicated Pelican satellites from Planet Labs; investor in iQPS; Itochu is 27% shareholder; other major shareholders include NTT Group (10%), Nippon Television Holdings (7.4%), and TBS Holdings (6.5%) |

| Kubota Corporation | 株式会社クボタ | has strong ties with DKB Group and Mizuho, but it operates more independently than most keiretsu members and regularly partners with Marubeni (Fuyo), Sompo Japan (Fuyo), and others; developing closed-loop agriculture systems for long-term space habitats; uses hyperspectral data to monitor soil health; digital twins of farms; autonomous agriculture equipment |

Kanematsu (兼松株式会社) began by importing Australian wool in 1889, expanded to wheat in 1900, and then became a more diversified trading company after WW II. Kanematsu is a second trading company that retains strong ties to the DKB Group, including a long-time banking relationship with Mizuho. However, it is somewhat more independent and serves as a neutral bridge to other keiretsu. It is an investor in Sierra Space, a partner on Sierra/Blue Origin Orbital Reef commercial space station and has facilitated IHI Aerospace providing the docking system for Orbital Reef.

Sanwa Group

As noted above under the Mitsubishi Group, this group shares a common core bank, Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group (MUFG), but it otherwise continues to operate within its own network including a president’s council known as Midori-kai.

| Company (English) | Company (Japanese) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sojitz Corporation | 双日株式会社 | anchor trading company for Sanwa Group after merger of Nichimen and Nissho-Iwai; partnership with Degas on geospatial foundation AI models; investor in Ricult |

| Sojitz Aerospace | 双日エアロスペース株式会社 | materials and components for solid rocket boosters; import and distribute satellite components |

It’s Complicated

The above list might suggest that the entire space and geospatial industries are coordinated through these large keiretsu networks. However, despite the above focus on the early history of the major zaibatsu industrial conglomerates and their evolution into the keiretsu networks after WW II and the U.S. Occupation, it is important to reemphasize a point from above: a combination of government regulation, mergers and acquisition, innovative startups, and the disintermediating force of the Internet have weakened keiretsu networks, and they are much less important today. Keiretsu ties have weakened since the 1990s in general, and most new firms cultivate relationships with multiple investors, trading companies, suppliers, and other strategic partners. Even when a startup is set up by a shōsha or another keiretsu firm, they frequently seek diverse additional investors. Even many century-old companies that arose in the zaibatsu era have remained independent and maintain financial, trading, and supplier relationships with a wide range of partners. A few examples follow.

IHI Corporation (株式会社IHI) (formerly Ishikawajima-Harima Heavy Industries (石川島播磨重工業株式会社) is a major industrial rival to Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI) and Kawasaki Heavy Industries (KHI), but while IHI has a venerable industrial history that stretches back to 1853, it has maintained relationships with all of the major sogo shosha and major banks. Its aerospace business was acquired from Nissan’s Aerospace and Defense Divisions to form IHI Aerospace. Today, it is a major manufacturer of rockets (Epsilon and KAIROS), payload fairings, sensors, and satellites and is an investor in startups such as SPACE ONE. It also has a partnership with Kanematsu and Sierra Space and also contributes to the HTV and HTV-X cargo spacecraft.

Toyota (トヨタ自動車 株式会社) - While the founder, Toyoda Sakichi, received early financial and business support from the Mitsui zaibatsu in developing his textile business, Toyota charted a course independent from Mitsui or other zaibatsu/keiretsu. Like many large manufacturers, it has built a so-called “vertical keiretsu” that consists of a hierarchical network of thousands of companies that supply parts, materials, and services to the main company. Today, Toyota is both an investor and manufacturer of space-rated materials and high profile projects like a pressurized lunar rover.

Honda (本田技研工業株式会社) - Like many rapidly growing manufacturing and technology firms established after WWW II, Honda is not associated with any keiretsu, and it has cultivated a reputation for nimble, innovative product development. Similar to Toyota, it has developed its own independent vertical keiretsu of suppliers. Its recent R&D work has focused on developing a reusable rocket, robotics, and space-grade fuel cells.

Toshiba (株式会社 東芝) previously built satellites in a joint venture with NEC (NEC TOSHIBA Space Systems) but now focuses on a few high value data, software and components. Toshiba was created in 1939 from a merger between Shibaura Engineering Works and Tokyo Electric. Shibaura had been a Mitsui company, and Mitsui Bank saved the company from insolvency in 1893. Tokyo Electric brought with it close ties with U.S. firm General Electric and banking relationships with both Fuyo and DKB Groups. So it has actually participated in the executive councils of Mitsui, Fuyo and DKB Groups, until it was taken private in 2023 and is now owned by a consortium of companies.

Furukawa Electric (古河電気工業株式会社) both leads its own historic Furukawa Group founded in 1875 and has deep ties to the DKB and Fuyo Groups. It manufactures superconducting wires; metals, polymers, photonics, high frequency materials, optical fiber/cables for high speed communications for ground stations, copper foil for batteries and semiconductors, heat pipes, and thermal management systems.

Nippon Steel (日本製鉄株式会社) is a core member of both the Fuyo and DKB Groups, participating in the president’s councils of both. Further, since its 2023 merger with Sumitomo Metal Industries, it also has strong ties with the Sumitomo Group. The firm creates long-span steel structures used in rocket vehicle assembly buildings, low expansion alloys used in spacecraft, polyimide for flexible printed circuits (FPCs) and stainless steel foil used in satellite and spacecraft; high performance steel components for rocket engines; and space-grade metal powders for 3D printing large rocket components (collaboration with Nikon).

Investing in Commercial Orbital Real Estate

Above, I mentioned that Mitsubishi Corporation (the Mitsubishi shōsha) had announced they were increasing their investment stake in the Starlab Space [Nikkei Asia]. They are not alone; two other Japanese trading companies, Mitsui & Co.(三井物産株式会社) and Kanematsu (兼松株式会社), are also investing in attempts to launch and build commercial space stations.

The Starlab Space effort is a consortium led by Voyager Technologies and Airbus along with Mitsubishi, MDA, Palantir, and Space Applications Services. The additional investment from Mitsubishi will make it the third largest shareholder. Starlab was started in the U.S., and the Airbus investment added a Germany-based joint venture in January. Based on that precedent, it's possible that the Mitsubishi investment will also result in a Japan joint venture to support some facets of the space station development. What does Mitsubishi get out of this? I think they want to be in charge of running the research lab on the Starlab space station. This would enable them to solicit contracts from organizations seeking to conduct research in orbit, and they would also presumably become a key supplier of materials, components, and resupply of the station.